St George, Dragons, And The English Part 3

Locating a contemporary relevance of the soldier Saint to the English people.

The words “he wasn’t even English” characterise the shallow critique from the cultural-left in response to English observances of St George’s Day.1 The vitriol so readily in evidence from this constituency reveals more than just enmity. It is indicative of a deep-seated frustration with the reality that the English people have an annual cultural day of our own that the left has only been able to attack and partially sideline rather than delegitimate.2 These people usually refrain from a meaningful attempt to appropriate St George’s Day for their own purposes as this is very obviously ideologically at variance with their efforts. When such attempts are made, they inevitably run aground, as will be shown. Although St George's Day is not grandly recognised in a mainstream sense, in the media, and in public, and left-wing criticism may have contributed to its diminution, there are other complex reasons for its current stature, and leftist designs have not extinguished its recognition on April 23. St George is not exclusively England’s Saint. However, he has a particularly strong rootedness in English culture. This history has formed a heritage strong enough to withstand efforts to divest St George's Day of its English character. The festival in some ways thrives in opposition to globalist and neoliberal imperatives.

St George and St George’s Day in English History

There is a long history of the English people marking St George’s Day. The Feast of St George was popular in the late medieval period and St George’s Day gained official status as a feast day in 1415,3the Synod of Oxford declared April 23 a holy day in 1222.4 Celebrations featured reenactments of the dragon-slaying.5

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, plays about St George occurred on May Day, a festival that welcomes spring and rejuvenation. Writing in the Journal of British Studies Muriel C Mclendon detects a theme of renewal tied to the Saint. It found currency among those closely involved in agriculture.6 An agrarian dimension to the legend of St George was noted in part two of this series.

Hanael Bianchi’s work cites records from the Royal Household. The documents show St George’s Day was only second to Christmas in terms of money spent on food, drink, and entertainment on the eve of the Reformation.7

After the upheaval, the event survived to varying degrees. It was eliminated from the Church calendar when saints’ days came under attack from Protestant reformers.8

With the Enlightenment, secularism emerged triumphant in the West. Seen in this light, a lack of willingness to celebrate a day dedicated to a saint can be understood. What about St Patrick’s Day observances in Britain? In some way, it is an exception to the point. It is a notable event in British public life. The wide observance of St Patrick's Day may be attributable to its historical function as a reaction to a dominant British identity. The Irish are a minority in Britain, and minorities can at times more eagerly feel a need to express their culture than those who belong to a culture pointed to as the dominant one in society. St Patrick’s Day is associated with drunken revelry in a way that St George’s Day is not. Drunken revelry does not require great powers of persuasion for the Irish and British public to indulge. This last factor is maybe the signal reason for the popularity of St Patrick’s Day in British society.

An English historical precedent exists for demographic pressure precipitating an assertion of ethnic and national pride. A revival of St George’s Day began in America in the eighteenth century following non-English immigration. Incomers lowered the English percentage of the white population in America from ninety percent in 1790 to sixty percent in 1820. The English formed societies, following the examples of other ethnic groups who had done the same. The Society of the Sons of St George was organised in Philadelphia in 1772. It had a charitable function that supported the English.9

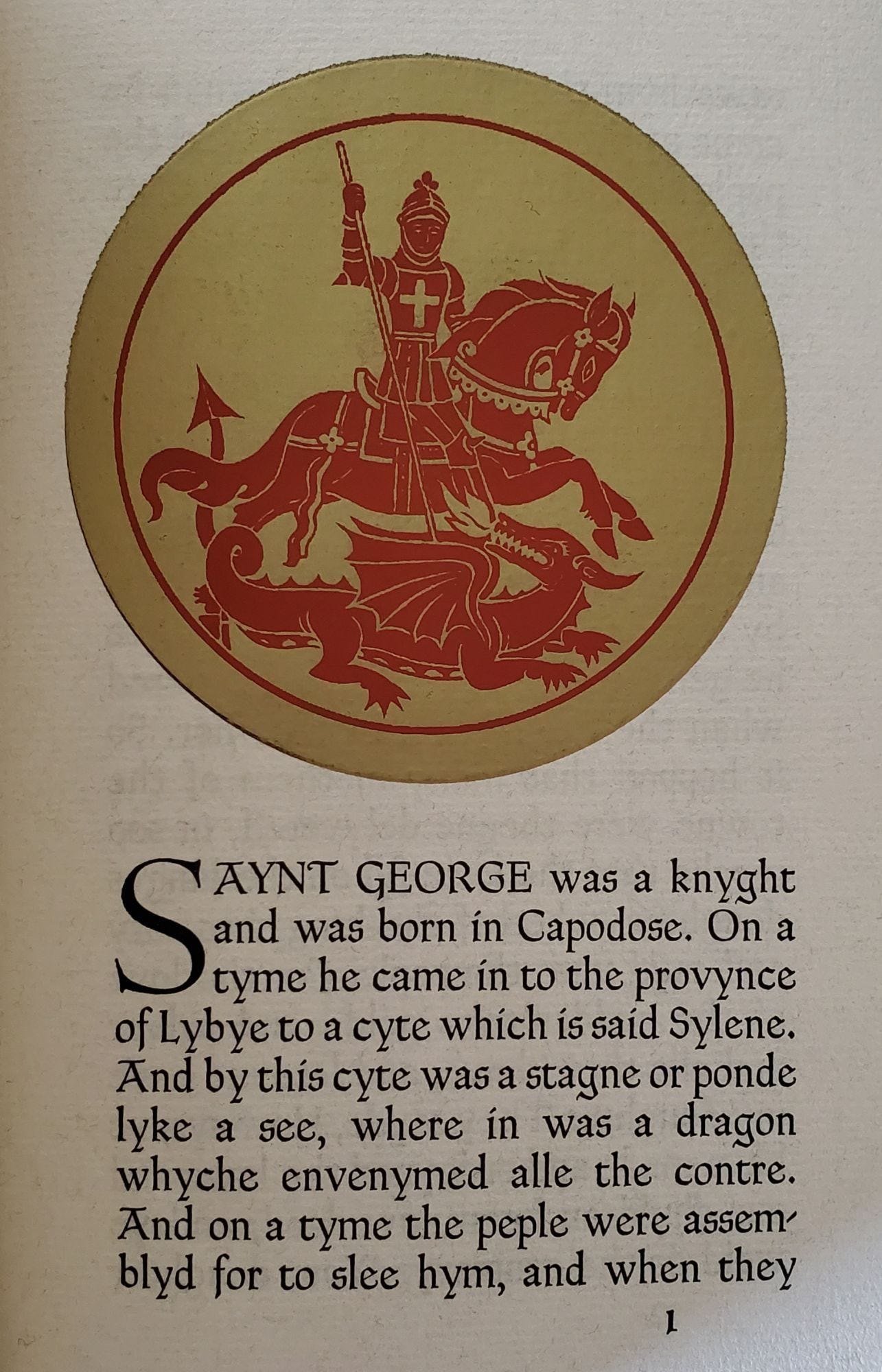

The connection between St George and the English long predates the early modern period. In The Golden Legend, William Caxton points to a calendar by the eighth-century English historian Bede that references the Saint. Edward III founded the Order of the Garter and a college in the castle of Windsor in St George's name. The Saint was said to have appeared to crusaders as they scaled walls at the siege of Antioch in the late eleventh century. This last factor, in particular, positions him against cultural relativism. His association with the Crusades relates him to an English historical experience.10 Famously, Shakespeare immortalised St George’s name as a war cry in Henry V.11

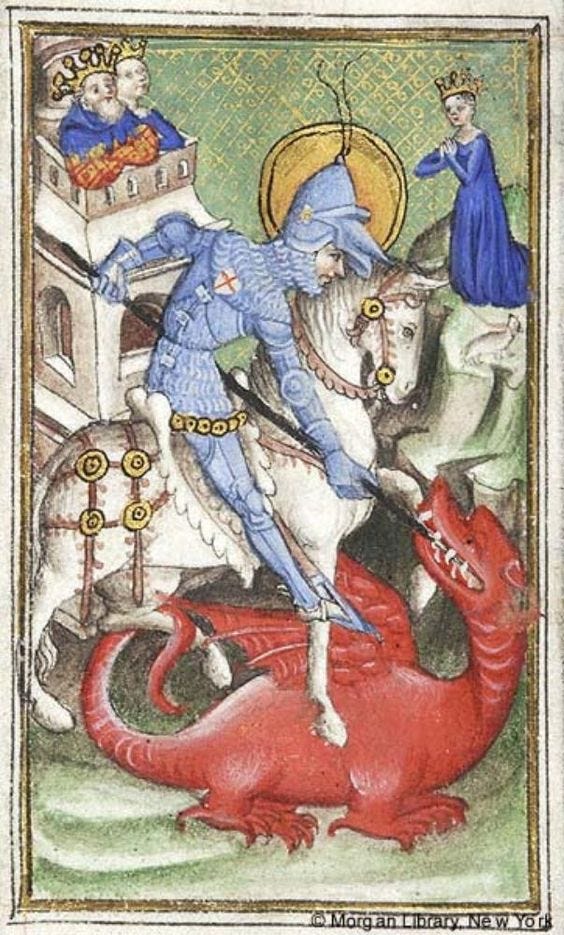

Similar victories to that won by St George have found a place in English folklore. The triumph of man over dragon is identifiable in English culture. In English celebrations, reenactments of the dragon-slaying have depicted St George in armor, on horseback, emblazoned with the Cross of St George. This emblem is also the national flag of England, and it appeared on crusade.12 This last signifier ensures that St George has what is understood today as a conspicuously English presentation.

A reason for the left's aversion to St George's Day is the link between the Cappadocian and the Crusades. They are reliant on Muslim votes and therefore eschew positive acknowledgment of the event.13 The left regards white ethnic identity with complete and utter contempt. St George’s Day is not for them.

An assault from The Independent on the English

The article, St George's Day: Six reasons why England’s patron saint is a symbol of multiculturalism, by Jon Stone, was published in The Independent on April 23, 2021. Stone notes St George was a Cappadocian. How does this make him a symbol of multiculturalism and not just one of Cappadocia for instance? Stone's claim was made next to a picture of Bengali street signs in London. The image implied that St George would have approved of a Bengali presence in Britain. The attempt to link England’s Patron Saint with the imposition of foreign street signs lays bare the intellectual sterility in evidence on the left.

Stone laughably claims St George moved from province to province as a ‘skilled manual worker travels between the member states of the EU to find better employment'. This is a grandiose anachronism. Only from the mind of a leftist whose lack of sense is like one who tries to convince himself that his chunk of chalk is the same as cheese because he is desperately hungry and wants to eat could such a statement come. Stone points to someone who might be an economic migrant engaging in manual labour, and of the twenty-first century in every way, including familiarity with modern technology such as mobile phones, the internet, and travel; he proceeded to link such a person with a Christian soldier and a religiously zealous life that entailed riding on horseback, carrying a lance, killing a dragon, conducting a mass baptism, and divinely confounding tormentors. He went beyond trying to draw on elements of the legend of St George that might be relevant today and instead opted for an ahistorical attempt at equivalence. Stone expressed a desire to strip an English national day of anything English. This led him to take vast leaps of the mind that would only find physical parallel if he stood at the edge of the Grand Canyon and tried to jump to the other side.

Stone noted that St George is claimed as the Patron Saint of diverse places. This is true. However, St George’s adoption by many nations is not a just cause to associate him with multiculturalism as it is understood today. He does not stand as an advocate for the unfettered introduction of divergent peoples and cultures into a country. The term multicultural is anachronistic when applied to pre-modern periods. Cultural fusion in antiquity would entail a markedly different complexity and character to that of the present.

St George’s zealous actions are the antithesis of cultural relativism and hence the modern dogma of multiculturalism. After saving Silene, St George does not tell the people to carry on practicing the spiritual ways they observed hitherto. He converts them to his religion. This act is in no way in keeping with a relativist approach.

Stone claims St George is a multicultural symbol because he endured persecution for his religious beliefs. How does an experience of persecution make one a multicultural symbol? The picture chosen by The Independent above this portion of the article shows someone wearing a niqab holding hands with a small child. The implication is that such people experience maltreatment for their religious beliefs. St George is associated with the Crusades and Christian proselytism. Amazingly, the paper compared him to contemporary Muslims. Can there be a more dissonant association? A picture showing Christian victims of religious discrimination would have been more appropriate, and recent images could demonstrate this point.

According to Stone, St George’s alleged multicultural attributes include service in the army of the Roman Empire. Stone stated that those under Roman rule were allowed to keep their local traditions. There is some truth to this. However, Stone still did not demonstrate how St George is a multicultural symbol. He never defines the term and fails to go into detail that might bolster his claims. Stone’s piece is an example of the weakness of the left when attempting to appropriate St George for their ideological positions. His efforts reveal desperation when seeking to reconcile the irreconcilable. The dissection of Stone’s article here has shown that St George’s Day can resist attempts to uproot it from English culture.

St George’s Day and opposition to globalism and neoliberalism

St George’s Day, in some ways, is situated in opposition to globalism and neoliberalism. Broadly, globalism can be said to reflect multinational institutions such as the United Nations, a foreign and economic policy enacted on a global scale, ease of communication, the salience of technology within our lives, and freer trade. It enables the dominance of wealthy multinational companies like Amazon, large-scale movements of people, and a blurring and erosion of national identities via the governmental instrument of citizenship. Globalism has many facets, not all necessarily bad.

The anchoring of St George in English culture supports parochial celebrations. By way of its national character, St George’s Day reacts against the ubiquity of today’s globalized world. Where globalism inevitably signals to the international, St George’s Day acknowledges the national. Globalism has enabled wealthy multinational companies; St George’s Day observances often involve fairs providing opportunities for smaller businesses. Such commerce allows people a greater chance to support people they know. It provides a facility for the affirmation of an English in-group preference.

An English in-group preference is in marked contrast to the support of international brands at variance with English interests. Major global corporations support policies that diminish national homogeneity. The unrestrained movement of labour is an example of this. Providing business to non-British companies furthers the development of bridgeheads between Britain and elsewhere. This process precipitates the erosion of national homogeneity. It is contrary to the English community's interests to adhere to such a state of affairs.

Activities evoking pre-modern elements and authentic culture often mark St George’s Day. Inside Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens in 2019, the St George’s Festival hosted a medieval tournament, hopscotch, falconry displays, traditional crafts, and reenactments of the dragon slaying. Mystique and magic counter the blandness of globalised society. St George’s Day functions can be found and enjoyed by those willing to look for them. The celebration might not be popular with much of the mainstream, but St George’s Day is still a significant event.

The English possess a rich and varied culture. Recognition of this heritage is a rejection of globalised processes that deracinate us; and it is more uplifting than your umpteenth Costa coffee and whatever you watched on Netflix last night. Some may proclaim themselves as ‘‘citizens of the world’’. Most people seek a more meaningful and distinct identity.

Like many traditional celebrations, the broader resonances of St George's Day oppose neoliberal imperatives in some way. The same might be said of its positioning towards other modern ideologies too. Neoliberalism extols the market and the individual above all other considerations. It sees economic competition not as a primary virtue but as the primary virtue. It relegates culture. It is consonant with the erosion of the sacral elements of Christmas by materialism. No such avaricious designs sully St George's Day. Festivities on April 23 reawaken a time predating the salience of modern market forces in a way that Christmas should but does not do in British society. The less commercial aspects of St George’s Day reflected in eschewing expense on gifts support an understanding within a rooted cultural collective. It stands in marked contrast to the reduction of people to mere cogs in a technocratic system. We are more than instruments for economic production, consumption, and compliance with hypochondriacal coronavirus edicts.

Conclusion

Analysis of Caxton’s work reveals the St George story commends helping the weak in the face of terror, diffusing Christianity, and spurning material wealth. In saving the princess, St George exemplifies gallantry and a traditional male gender role. The portrayal of the Saint shows many chivalric resonances. The association of chivalry with discipline, physical fitness, and social advance by merit are highly relatable today; chivalric qualities of loyalty, honesty, dedication, courtesy, and courage transcend time. The accomplishment of initiatory challenges in the chivalric world can be related to surmounting obstacles in any epoch. St George’s traits and attributes and his emphatic Christian message ensure the Saint stands as an antithesis to cultural relativism.

St George is avowedly Christian. However, the act of slaying a dragon is an ancient feature of cultures all over the world and is unconfined by religious doctrine. The heroic defeat of dragons that assail and rape females is central to myths involving the beast. This knowledge provides deep meaning to the legend of St George, pertinent to efforts against those who assail, violate, and kill today.

Myths have recorded adventures of protagonists seeking to capture gold and water from the creature. Tales of dragons are allegories of feats we need to achieve to fulfill dreams. The dragon stands for obstacles to overcome. Success following trials resonates with the culture of chivalry, St George, and his deeds.

Dragon stories exist within English folklore. Myths involving the creature may be a global feature though there are distinguishably English legends involving the fire-breathing foe. In these tales, dragons beset cattle and livestock as well as humans. Dragon slayers curtailed threats to agricultural life. These examples identify folk heroes with the provision of food and complement the aforementioned provision of water. The rural setting of feats achieved by men like Shonks evokes a countryside now receding with the advance of urbanisation. Our folklore recalls pre-modern ideals that can react against such developments today.

There is a rich tradition of St George’s Day observances in England. References to it within our history enhance the strength of St George as a figure arrayed against cultural relativism, via dint of English cultural specificity. The potential for St George’s Day to operate as a beacon for patriotic interests that react against left-wing agendas is clear. The above dissection of a poor attempt to appropriate St George for leftist motives attests to the implausibility of positioning England’s Patron Saint against an English national interest.

St George’s Day celebrations provide an opportunity to affirm an in-group preference. It reacts against facets of globalism and neoliberalism not conducive to English interests. It achieves this through recognition of a rooted culture and pre-modern elements which precede a time before the salience of modern market forces and unfettered immigration. The festival has not been divested of its meaning by commercialism. St George’s Day is an opportunity for coming together in a culturally specific English context.

The findings of this series should concern anyone who desires an English cultural revival. English writers, artists, playwrights, screenwriters, architects, podcasters, video-makers, and architects, have a rich cultural reservoir. St George's Day gatherings should serve as a locus for these energies to be displayed, encouraged, and celebrated. As a rule, we should never let April 23 pass by without fuss, no matter where we are.

References & Notes

St George's Day: England's patron saint is a perfect symbol of multiculturalism | The Independent

In this piece, I use terms such as cultural-left, left, and leftist. These terms are generic and apply to a broad body of left-wing thinking rather than the designation of a particular group or specific set of policy positions. At the top of this post, the term ‘cultural left’ is used, this is the most accurate designator of the leftism herein described. This term acknowledges a possibility that there may be a left that does not concur with the left-wing cultural positions reported above. However, the current cultural beliefs and ideas so prevalent in left-wing thought are of such a prominence that broad terms can be fairly applied.

Jack Montgomery, Left Celebrate St George's Day with Annual Lie He was 'Turkish Immigrant' (breitbart.com) 22/4/22. See this piece for examples of left-wing assaults on St George’s Day.

Muriel c Mclendon, A moveable feast: Saint George's Day Celebrations and Religious Change in Early Modern England, Journal of British Studies, vol 38, no 1 Jan 1999, 4

Ibid 7

Ibid 4

Ibid 8-9

Hanael P Bianchi, The St George's Society of New York and the Resurgence of England's National Holiday, New York History, Vil.92, No.1/2, 2011, 54

Ibid 56-57

Mclendon 4

William Caxton, The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints, Volume Three, 1900, 133

William Shakespeare, Henry V, New York University Society, 1901, 59-60

For a depiction of St George on horseback, in armour, and with a spear, see the painting Saint George and the Dragon, Raphael, c. 1506 pictured in part two of this series and easily found by a search on Google. Also see the painting Saint George and the Dragon by the Master of Sir John Fastolf, c. 1430–40; in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, linked to here: Saint George | Facts, Legends, & Feast Day | Britannica, and pictured in this piece.

Stephen Tall, Bradford West by-election: 5 initial thoughts on an astonishing result, (libdemvoice.org) 30/3/2012. This article provides detail of a strikingly fawning letter from George Galloway.