St George, Dragons, And The English Part 2

Locating a contemporary relevance of the soldier Saint to the English people.

Game of Thrones, Pokemon, Dragon Ball Z, and Harry Potter are among a litany of well known creative contributions in popular culture to have featured dragons. The prominence of the beast in books and television and its widespread representation on merchandise flagrantly attests to the mystique of these fire-breathing monsters and their capacity to spark and ignite the human mind. The creature has been imagined for thousands of years and the Christian legend of St George defeating a dragon has parallels across many cultures and civilisations that long predate Christianity. A knight on horseback killing a dragon and saving a maiden with a fortified town in the background has been a cultural theme since ancient times.1

In an extensive piece in Anthropos, Robert Blust detects the first representation of a dragon as a horned serpent in the earliest Babylonian conception of Tiamat, the spirit of chaos in the primeval ocean. His work features a table recording dragon traits in Europe, the Near East (including Egypt), the Far East, Mesoamerica, and North America. In all these regions the creature has been perceived as a guardian of springs, in every region except Europe dragons are a giver and a withholder of rain, in every region except North America, they are capable of flight. In all places except Mesoamerica, the dragon exists in opposition to thunder and lightning and the sun. In India and the Near East, dragons are not depicted as red. Only in Europe and India are dragons connected with immortality, and only in Europe and the Near East are dragons attributed capacity to encircle the whole world. In Europe, India and the Far East dragons have fiery breath. Blust’s study reveals variations in dragon traits across the world. However, a remarkable commonality also emerges in conceptions of the beast. Dragons in all the regions in Blust’s table have been said to have scales.2

Babylonian dragons of early creation myths were not wholly evil and were sometimes morally ambivalent. Although it would seem that most often the beast has been portrayed as a scourge of humankind. In Iroquois legend, He-no saves a girl pursued by a dragon by striking the creature dead with a thunderbolt. In European legend, a serpent is killed by Thor the Nordic God of Thunder. In North American myth the dragon seeks regularly to ravish females. Among the Mountain Arapesh of New Guinea, the dragon is associated with rape. It is hostile to menstruating, pregnant women, and men and women after intercourse. Penalties imposed by the dragon following infringement of these taboos include raping a woman until she dies and injuring through rape the unborn child of a pregnant woman so that it is miscarried or made a monster. Hostility directed from dragons towards menstruating women is also a feature of Brazilian myths where pubescent girls are the subject of bestial attempts at sexual interference.3

Dragons are intimately tied to water. In non-European cultures, such as that of the Pueblo in North America water-serpents are associated with withholding rains. According to a folk belief among the Chinese in Gansu province, the rainbow is an enormous dragon that drinks from the sea. Francis Huxley has written of twentieth-century Macedonians believing in horned serpents guarding springs. The creature has been portrayed protecting gold by caves near waterfalls.4

Blust points to a link between the rainbow and the dragon. He cites various tribes' myths that viewed the rainbow as a predatory dragon or rainbow serpent. The end of a rainbow touches a spring where gold is commonly found in small amounts of alluvial river washings. It makes sense, following this logic, that dragons would be associated with gold. Blust argues that urbanisation, agriculture, and literacy are among the factors that occasioned a split in the perception of dragons. This led to two main conceptions of the creature, one as a red, more upright entity, and the other as a cylindrical rainbow serpent. The view of the rainbow in Christianity may also have something to do with this; in the Bible, it is associated with God’s protection.5 This would explain why the image of the dragon in Western culture as a red, ferocious, and demonic behemoth has become a stock image of the beast, as this appearance is alien to the symbol of the rainbow and hence its Christian associations.

How exactly the concept of a dragon has become renowned worldwide, we cannot say for certain. What we do know is that the messages conveyed by myths epitomise fighting a just cause to protect others, and the will to defeat, through courage, an unjust and redoubtable aggressor posing grave danger. The liberation of the princess by St George is profoundly symbolic when viewed in conjunction with the propensity of dragons to set about the systematic defilement and rape of females. In this circumstance, the consequence of the clash with the dragon is of great severity. In consigning the dragon to death, St George’s triumph resonates with any efforts arrayed towards the defeat and liquidation of those who prey, assail, violate and kill today. In vanquishing the dragon, St George embodies justice, virtue, and humanity conquering nefarious forces.

Myths of dragons withholding water from humans and protecting gold and treasure bestow further significance on the already substantial meaning discernible from stories involving the creature. The need to acquire water to drink is inextricably tied to our instinct to preserve and sustain life. In a Greek myth, King Cadmus, founder of the city of Thebes kills a dragon with a rock after his companions had been slain by the beast when seeking to collect water from a spring.6 Cadmus's killing of a dragon signifies triumph over forces that aim to deprive us of what we need to survive. The penchant of dragons to guard what is alluringly sought by man is given expression in the Greek story of Jason and the Golden Fleece, and the dragons guarding treasure in the Old English epic Beowulf.7

Tales of dragons holding gold and treasure are allegories which tell of the courage needed to accomplish goals and fulfil dreams. In this light, the fight with the dragon is our willingness and determination to strive for what we want and desire. Although the odds may be stacked against us, and although we may feel fear, bravery, especially when allied to skill, can steer us to victory. Such stories offer relativity unconfined by religious doctrine.

The dragon is symbolic of obstacles in our way that must be overcome to ensure our wellbeing and happiness, and that of those we care about. Myths involving the creature signal the justice of fighting a cause for others and oneself. If there is something we want to achieve but have not, be this for a lack of courage or avoidance, or any number of reasons, the resolve and focus needed to do this is what will defeat the dragon that stalks our consciousness. In chivalry, initiation represented a break with an older, more limited self, and the becoming of a more accomplished and complete self (see part 1). Similarly, the destruction of the dragon may be symbolic of the evaporation of a prior incapacity, the shedding of a poorer state of being for a greater one. In the stories discussed here the dragon slayer realises a monumental feat and through this an especial eminence. “Killing the dragon,” can be an idiom for overcoming what was perceived as foreboding and insurmountable.

Stories where man triumphs over dragon are by no means a Christian conception. It stands to reason that adventures of this kind can be a source of meaning for pagans and those of any number of persuasions. A day to reflect on what it is that the dragon keeps from us, and the symbolic interpretations this might engender, provides a date in the calendar for reflection, appraisal, and resolution.

Similar victories to Cadmus's feature in tales from legendary Britain. A legend from Bisterne, Hampshire tells of a dragon plaguing men and cattle, the monster spoiled many who sought to thwart it. However, thanks to Sir Maurice de Berkeley the creature was overcome. The story comes to us in a document from Berkeley Castle dated to 1618. It references an earlier source from which it came. The record states the account was commonly known at this time. In battle, Berkeley kills the dragon but dies from injuries sustained in combat. A later version has Berkeley arrive with his sword, a glass case, and a jug of milk. He pours the milk into cans and hides inside the case; the dragon is killed while lapping up the milk. In another version, Berkeley is accompanied to battle by two dogs that also perish in the conflict. These dogs may be represented by the statues of two dogs at Bisterne Manor. Dogs fighting alongside man is a motif of stories pitting man against a dragon; faithful hounds assist dragon-slayers in the French medieval romance The Dragon of Rhodes. Representations of dogs often accompany dragon-slayers on tombs for the latter. Jennifer Westwood in A Guide to Legendary Britain reasons that this story was a ‘charter myth'. Such myths were used to explain how a family came by a piece of land or heraldic symbol. The Berkeley descendants bore a dragon on their coat of arms.8

In the deep recesses of St Mary’s Church in Pelham Hertfordshire rests a tomb purporting to be that of an eleventh-century lord of the manor Piers Shonks. At the centre of a black marble memorial, the staff of a tall cross is thrust into the jaws of a dragon. Legend has it that Shonks was a giant who dwelled in the parish and defeated another giant from Barkway, after this event Barkway paid Pelham quit rent. In a story well known at the end of the nineteenth century, a dragon had a lair under a yew tree. It terrorised the district until one day Shonks equipped with armour and sword, and aside three dogs, met the dragon and ended a fierce battle by driving his spear down the throat of the monster to destroy it.9 Like Berkeley Shonks died shortly after combat.

As in the lore of Berkeley, that of Shonks may also have developed to confer status. In Shonks's case, the tale may relate to property ownership. Westwood cites John Weever’s Ancient Funeral Monuments (1631) that states a family named Shank held property in Brent Pelham in the fourteenth century. This included ‘an ancient decaied house, well moated called, O Piers Shoonkes’. A moated barn known as Shonks Barn still stood in the area in the early eighteenth century. Westwood writes that Peter Shank, who was the benefactor of a manorial grant by Richard Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel, was the person referred to as Piers. She does not reinforce this view. In any case, the name Shonks or Shoonkes endured, and it would seem very likely that both the barn and the house relate to the dragon-slayer.10

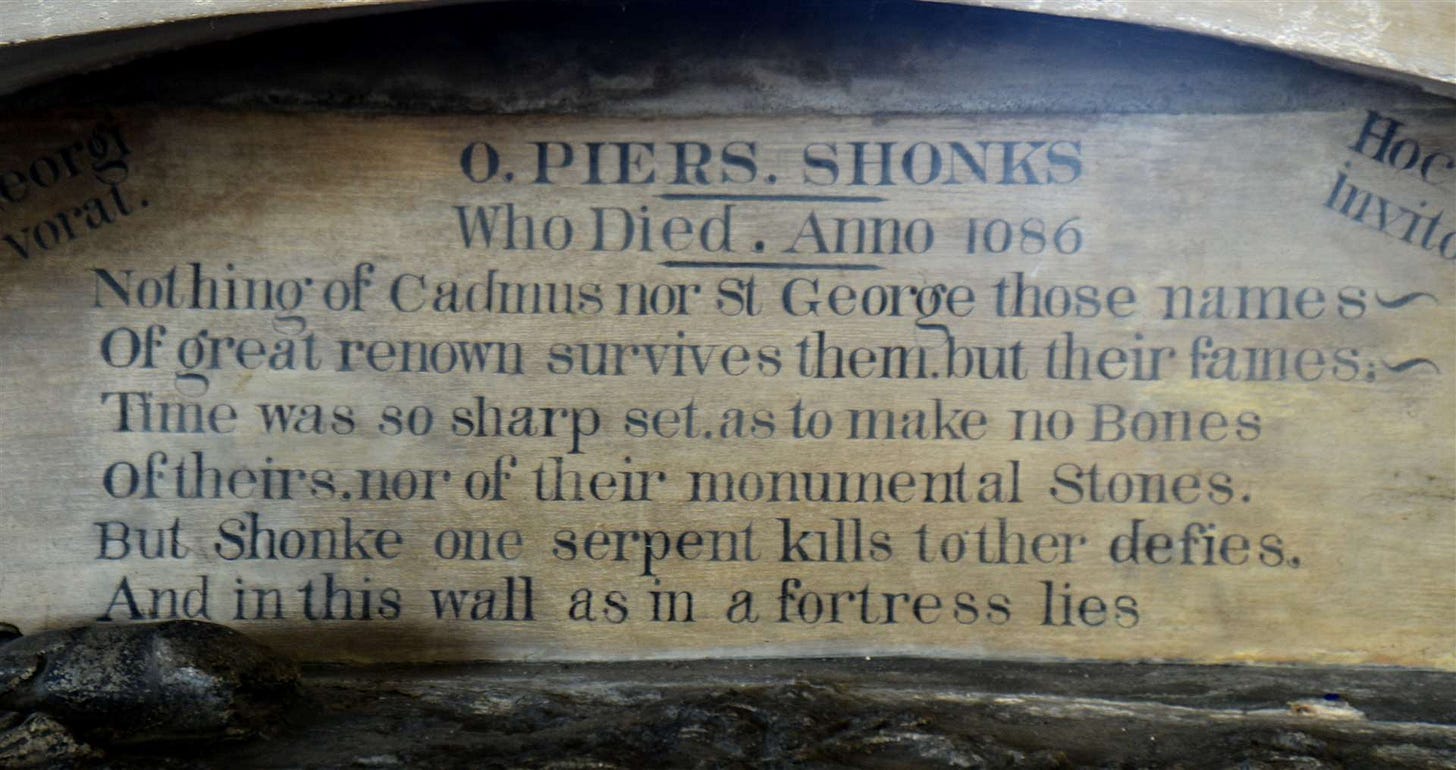

On the wall behind Shonks’s tomb, a Latin inscription is etched. An English translation reads:

Nothing of Cadmus nor St George, those names

Of great renown, survives them but their fames:

Time was so sharp set as to make no bones

Of theirs, nor of their monumental stones.

But Shonks one serpent kills, to’ ther defies,

And in this wall as in a fortress lies.11

In his History of Hertfordshire (1728), Nathaniel Salmon suggests that the verses were written by a former vicar of Brent, Pelham, named Raphael Keen, who died in 1614. The main part of Shonks’s tomb dates from the thirteenth century, the brick base and arch above it seem to be Tudor work. Keen knew of the legend, and someone, perhaps himself, deemed Shonks’s tomb to be worthy of restoration. When it was opened, unusually large bones were said to have been found. This lends support to the claim that Shonks was particularly large.12 Whoever Shonks truly was, and whatever he truly did, his reputed exploits have captivated minds for centuries.

In Deerhurst Gloucestershire, a ‘serpent of prodigious bigness’ is said to have poisoned inhabitants, killing their cattle. The people petitioned the king. A proclamation was issued, it declared anyone who would kill the serpent should enjoy an estate on Walton Hill, in the parish which then belonged to the English Crown. It is clear from the outset of this tale that it has been devised to legitimate a grant of property. John Smith a labourer, finds the serpent in the sun, with its scales ruffled up, he decapitated it with his ax, so reads a 1712 account. This legend has been kept alive by, ‘ferocious animal heads’ carved in stone on Deerhurst’s Anglo-Saxon church. ‘One or all of these are said to be the Deerhurst Dragon.’13

British folklore comprises a stock of dragon stories emerging centuries after St George. Therein the monster is the primary antagonist. Berkeley, Shonks, and Smith defeat dragons that had terrorised their locality. In the case of the stories featuring Berkeley and Smith, the dragons beset cattle and humans. This also occurs in the story of St George, where the dragon devours livestock. Dragon slayers stood for the heroic deliverance of people from being bloodily digested. They also curtailed a disruption to agrarian life through their fortitude. Hence, dragon slaying is bound with the provision of food as well as water. The name George means farmer, this bolsters the agricultural dimension of myths where the defeat of a dragon is a pointed imperative.14 It does not matter a great deal that these stories were likely concocted to confer status, property, or prestige on their subjects. The deeper resonances of the recollections have been impactive enough for these tales to live in folk tradition through the ages. In an English context, dragon slayers have often had canine companions by their side in battle. The English affinity with dogs today lends a pertinence to the closeness of dog and man in the tumult of folklore.

Heroic stories situated in a pre-industrial and pre-modern context recall a rural heritage. In many parts today, this ruralness is swallowed by concrete buildings, and rushing, swarming masses that envelop our cities. The agricultural and rural facets of the St George legend, and similar tales, can enlarge and sustain a cultural ideal that reacts against the celerity and cacophony of today’s city life. This dimension to the legend might serve a purpose in the present.

To be continued in part three…..

I had hoped I would finish this piece before St George’s Day, so sorry this was not the case, it is here now! I also expected that this would be the final part, however, more on matters about the place of St George’s Day in our own time will be the subject of what will be the last part of this series. And of course, part three will contain the series conclusion.

Pasquale Maria Morabito, Saint George and the Dragon: Cult, Culture, an a Foundation of the City, contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis, Culture Vol.18 (2011), 138

Robert Blust, The Origins of Dragons, Anthropos Bd. 95, H. 2. (2000), pp. 519-536, 521-520: Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "dragon". Encyclopedia Britannica, 7 May. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/dragon-mythological-creature. Accessed 25 April 2022.

Ibid 523, 527, 530-531

Ibid 526 527, 521

Ibid 527, 531, 532: for the association between dragons, the rainbow and rainbow serpents see Blust’s piece in Anthropos.

Ibid 527

Ibid 527

Jennifer Westwood, Albion: A Guide to Legendary Britain, 1986, 45

Ibid 106-108

Ibid 106

Ibid 107

Ibid 107-108

Ibid 250

Morabito 147