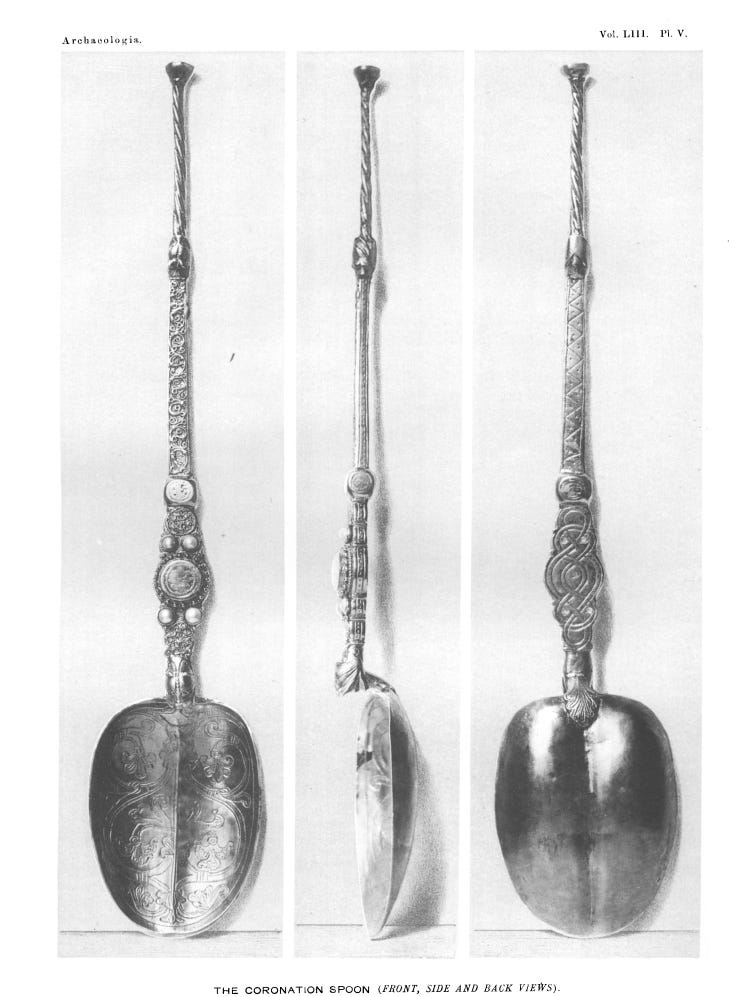

The sliver-gilt spoon on which chrism rests before the anointing of the British Monarch at the coronation ceremony is known as the only item of the British regalia to survive the destruction of the jewels ordered by the Commonwealth regime in 1649. Those who saw the coverage of the recent Coronation on GB News may recall historian David Starkey saying this.1 C.J Jackson, Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries (FSA), writing in an 1892 edition of the journal Archaeologia, the first journal of the Society of Antiquaries of London, refutes the claim that the current coronation spoon was made anew at the time of the Restoration. Ahead of the Coronation of Charles II, an enumeration of items to be made for that event does make mention of a spoon. Still, according to Jackson, this does not mean there was a replacement. To support this conclusion, he avers that the ornamentation of the Coronation Spoon is unlike goldsmith work at the time of Charles II. He states:

‘its pattern so closely resembles the pattern on a mitre of St Thomas of Canterbury, preserved at Sens, as almost to suggest that the design of both originated in the same source. The same kind of ornamentation may be seen also on the drapery of the statues of Clovis I. and his queen, which formerly stood at the entrance of the church of Notre Dame at Corbeil, which is twelfth-century work. Again, there is somewhat similar ornamentation, but ruder, being earlier work, on a gold frontal or table, presented to the cathedral church of Basle in the eleventh century by the emperor Henry II., and now preserved in the Cluny Museum. Moreover the same style of ornament is frequently found in the architecture of the twelfth century, but in none of the seventeenth century.’2

Of the spoon on the list of items to be made ahead of the Coronation of Charles II, he said: ‘The sum (£2) set down for silver and workmanship seems very inadequate for such a highly ornate spoon, even at that time. Moreover, the fact that no mention is made of the pearls, the gilding, and the enamelling, with which it was enriched, seems to indicate that the entry in question referred to another spoon made for the occasion, but which was probably discarded on the original spoon being subsequently brought to light. Taken altogether the weight of evidence seems to point to the twelfth century, rather than the seventeenth, as the date of the fabrication of this important item of our coronation regalia.’3

Other works attest to this view, including Crowns & Coronations: a history of regalia, by William Jones FSA, written in 1883, and The English Regalia, written by Cyril Davenport in 1897.4

Although confident of the twelfth-century origin of the spoon, Jackson does state: ‘It should however be observed that the shape of the bowl differs from that of the earliest known medieval domestic spoon, and except that it is wider in proportion near the stem, and altogether more shovel-like in form, it resembles somewhat the shape of the spoons of Charles II's time. On the other hand the manner in which the stem is joined to the bowl looks like a modification of the " keel and disc " feature of the early Christian spoons.’

The 1649 list ordering regalia to be broken up or melted does mention the spoon.5 In Crowning the King by Allied Newspapers Limited, the likely reason for its preservation in 1649 is explained by the object being in the ecclesiastical treasury of Westminster Abbey, and that therefore, it was not recognised as royal property, and spared destruction. Edward the Confessor deposited the regalia at Westminster Abbey, where it was until the ruination ordered by the Commonwealth.6 Maybe those searching for the spoon did not find it, and no one chose to keep it. As Jackson suggests, the object may have reemerged by chance. Other accounts, including that of David Hilliam in Crown, Orb, and Sceptre, credit the survival of the spoon to its purchase by Clement Kynnersley, once Yeoman of His Majesty’s Wardrobe. Hilliam says the spoon was returned to Charles II at the time of the Restoration.7

At the coronation, the Ampulla contains the chrism used to anoint the monarch. A screw allows the eagle head to be removed and liquid to be put inside it. The ornament used at the Coronation of Charles III is said by some to have been made anew in the seventeenth century; this view is contradicted. The eagle is conspicuous by its absence in the 1649 list of regalia set for demolition. Jones and Allied Newspapers Limited say that the existing eagle is the same as that used at the Coronation of Henry IV in 1399.8 In The English Regalia, Davenport reasons that the object weighing ten ounces of solid gold contains parts originating before and after 1649. He states that the pedestal is clearly of seventeenth-century origin. Davenport finds the whole bird ‘has been gone over with chased work, probably at the same period’.9 Although the general form of the bird was ‘made at a much earlier time, especially the body’, and the primitive screw on the neck; long predates the reign of Charles II.10 Hilliam agrees with this view, writing that ‘the eagle’s head and body date to the late fourteenth century’.11 Hilliam does assert that the Ampulla was 'made for the Coronation of Charles II in 1661, to replace the Ampulla destroyed by the Parliamentarians’.12 If this is what happened, then the reason for the head and body surviving seem odd. It is highly unlikely that the object was broken in part. Allied Newspapers Limited reason that like the spoon, the Ampulla was found in the Westminster Abbey treasury in time for the Coronation of Charles II.13 This account seems plausible.

Like St Edward’s Sapphire, discussed in part one, the Ampulla has a legend. The Virgin Mary is said to have given holy cream to St. Thomas of Canterbury. The cream was preserved in the golden eagle.

The only Christian kings anointed were those of England, France, Jerusalem, Sicily, and later the kings of Scotland, as these rulers enjoyed special papal favour. Kings of England and France had a special right to anointment with the holy cream or chrism, a sacred unguent made chiefly of olive oil and balm, and only to be used in the most sacred ceremonies of the church. ‘The eagle itself is an emblem of imperial domination. It may be an indication of the ancient claim of the sovereigns of England to be Emperors of Britain and Lords Paramount of all the islands of the West.’14

The eagle was the standard of the Roman emperors. After his coronation on Christmas Day 800, Charlemagne, claiming to be the successor of the Roman emperors, adopted the eagle as his ensign and had one placed on his palace at Aachen. In A treatise on heraldry, British and foreign: with English and French glossaries, 1892, by John Woodward and George Burnett, the writers state that the imperial seal on which the eagle first appears is that of Holy Roman Emperor Henry III, who reigned between 1039-56. The symbol of the eagle is synonymous with the Holy Roman Empire. Godfrey of Bouillon bore a banner displaying the eagle at a battle in 1080. He later became the first Christian king of Jerusalem.15

The image of the eagle on the Coat of Arms of the Holy Roman Empire signified rightful succession to the Roman Empire. A similar claim of the heir to Rome inspired the Russian adoption of the eagle. Following the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the Grand Dukes of Muscovy saw themselves as the inheritors of Byzantine heritage, hence the expression ‘Third Rome’ and its prominence within Russian and European historiography.16

It is fitting that the oldest parts of the regalia are used to perform arguably the most special part of the coronation ceremony, the anointing of the sovereign. The earliest detailed mention of anointing rulers is in the Bible.17 To anoint Charles III, the Archbishop of Canterbury put his fingers into the Coronation Spoon after chrism came from the beak of the Ampulla. He then placed the chrism on Charles’s hands, head, and breast. The anointing occurs in private behind a screen. The ceremony is especially sacred for the monarch as the Supreme Governor of the Church of England.18

To be continued in part three.

GB News, The Coronation of King Charles III, Saturday 6th of May, 06/05/2023, The Coronation of King Charles III | Saturday 6th May - YouTube

C J Jackson, IV.—The Spoon and its history; its form, material, and development, more particularly in England. Archaeologia, 53(1), 107-146, 119, 1892

Ibid 119

William Jones, Crowns & Coronations: a history of regalia, 1883, 73: Cyril Davenport, The English Regalia, 31

Cyril Davenport, The English Regalia, 1897, 4

Allied Newspapers Limited, Crowning the King, 1937, 97, 113-114

David Hilliam, Crown, Orb, and Sceptre: The true stories of English Coronations, 2009, (first published 2001), 231: Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 6, 1643, House of Lords Journal Volume 6: 29 September 1643' p. 235. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/lords-jrnl/vol6/p235 [accessed 23 July 2023].

Ibid 113: Jones, 73

Davenport 28-29

Ibid, 29

Hilliam 230

Ibid 230

Allied Newspapers Limited 113-114

Davenport 28

John Woodward, George Burnett, A treatise on heraldry, British and foreign: with English and French glossaries, 1892, 242

One relevant article on the subject of the ‘Third Rome’: Dimitri Stremooukhoff, Moscow the Third Rome: Sources of the Doctrine, Speculum, 28 (1), 84-101. To find out more about the symbology of the eagle see Rudolf Wittkower’s, Eagle and Serpent. A Study in the Migration of Symbols. Journal of the Warburg Institute, vol. 2, no. 4, 1939, pp. 293–325. https://doi.org/10.2307/750041. Accessed 23 July 2023, and Justin S Hayes’s, Jupiter 's Legacy: The Symbol of the Eagle and Thunderbolt in Antiquity and Their Appropriation by Revolutionary America and Nazi Germany, Vassar College Digital Window, 2014

Allied Newspapers Limited 113

Hilliam, 230: GB News, The Coronation of King Charles III 06/05/2023-YouTube

Fascinating. I didn't know that anointment was limited to such a small number among European monarchs.