The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (Chronicles) is the most famous work associated with Alfred the Great and his reign as King of Wessex between 878-899. The Chronicles began in the ninth century and continued as a living, breathing document well into the twelfth century. Who produced and disseminated the Chronicles and for what purpose?

Historian Nicholas Brooks has found that from the 890s until 1131 sections of the Chronicles continued to be disseminated intermittently from the royal household. He states that the sustained royal focus of the Chronicles ‘would reflect the career interests of those in the king’s service; and the local continuation of manuscripts would reflect such men’s role in the abbatial or episcopal office’.1

Simon Keynes points to the multiplication of copies of a common stock of the Chronicles, implying distribution for a shared demand and a particular purpose. The existence of seven copies of the Chronicles that are identical to 891 before they diverge, points to a policy to preserve the early portion of the text and allow for regional continuations.2

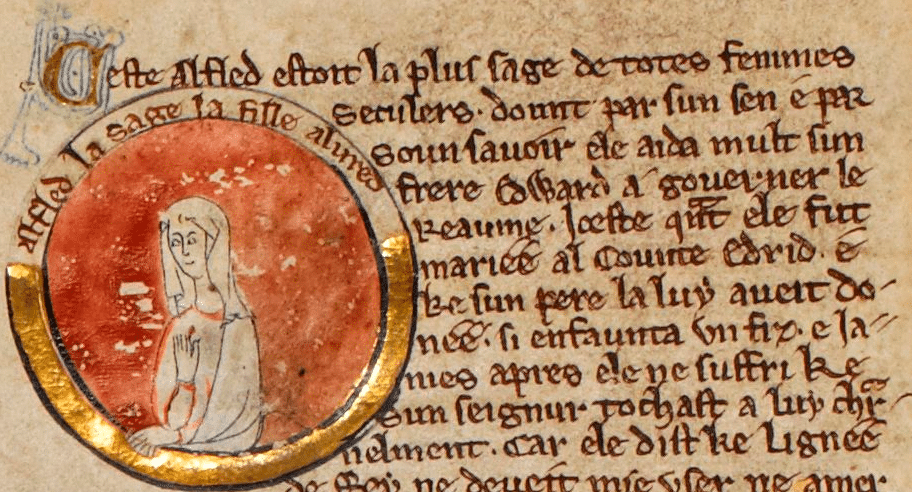

The phase of the Chronicles dealing with the reign of Alfred’s father Aethelwulf, up until Alfred’s death, indicates that the annalistic enterprise began with Alfred’s court. This was in accord with his dynastic interests. According to the Chronicles, Alfred was to Rome by his father in 853 and consecrated as king by Pope Leo IV, although Alfred had elder brothers.3 Historian R.H.C Davis has pointed to a letter of Pope Leo IV that states he ‘decorated him as a spiritual son with the dignity of the belt and the vestments of the consulate’.4 Davis opines that Alfred had stood to gain from what reads as a misstatement in the Chronicles. He finds cause to believe that Alfred wrote the Chronicles in a general sense. While the latter view seems plausible, the implication that Alfred deliberately falsified an account of consecration in Rome that occurred when he was a small child so that he could justify his position as king, or just for his broader self-interest, is mistaken. It is important to be mindful that Alfred’s father Aethelwulf had experienced a sub-kingship. This entailed powers of rulership granted by a more regal authority.5 Aethelwulf employed this mode of delegating command when he made his son Athelstan ruler of Kent, Surrey, and Sussex upon acceding to the kingdom of Wessex.6 This considered, it is not impossible to believe that Alfred may have been anointed for some authoritative role he would accede to when he came of age, perhaps a sub-kingship of sorts. The interpretation of the consecration as a falsified expression on the part of Alfred, of the desire of Aethelwulf at Rome, to bequeath his kingdom indivisibly to Alfred is problematic. If we believe this then we may also believe that Alfred felt compelled to make such an outlandish fabrication when he was already a king and living in a time where inheritance was often complex and primogeniture was by no means a given.

The description of consecration in the Chronicles seems to have been undertaken to embellish Alfred’s status and to enhance a sense of mystique around him, linking his person and his people with the Classical world. This was what the famous translation programme of learned Latin works attributed to Alfred had done with the rendering of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy which is set in Rome.7 Such an adaption of events and the laconic manner in which they were recorded may have met with the approval of Alfred and an editor. A team of editors may have been at work and they may have felt such an economy with the truth would not undermine the historicity of the enterprise. This summation is more plausible than Davis’s view of the recollection of consecration being ‘the most significant indication of Alfred’s authorship of the Chronicle’.8

Alfred’s will cites his father’s bequest, unfortunately this has not survived for the perusal of historians today. At the beginning of Alfred’s endowment a passage reads, ‘my father, King Aethelwulf, bequeathed to us three brothers, Aethelbald, Ethelred and myself; that whichever of us should live longest was to succeed to the whole’.9 This may have meant Aethulwulf’s last surviving son would inherit the whole of the kingdom of Wessex. With this in mind, an embellishment of the account in the Chronicles of Alfred’s journey to Rome does not have to read as extravagantly as it has done for some. As the fourth son, Alfred may have been expected at some point to receive a kingly inheritance if he outlived his brothers, through the office of king passing between siblings rather than through primogeniture.

The inclusion in the Chronicles of Alfred’s journey to Rome and the meeting with the Pope may have been intended to signify that the acquaintance of the young Alfred with the pontiff had lent Alfred a providential hand. This had manifested not only in Alfred’s rise to the kingship of his people, who were unified under him, but also in him overcoming heathen foes on the battlefield.

The account of consecration neatly ties in with the Christian teleology of written works associated with Alfred. It is this last point that Davis misses when he writes, ‘It is very difficult not to think that the writer wanted us to imagine that King Aethelwulf had already recognised Alfred’s quality and intended him to be his heir. We are not reminded that at that date Alfred was only four years old, that he was only the fourth son, or that his three elder brothers did succeed to the throne in turn before him. On the contrary, the main effect is gained by one positive error of fact’.10 The writer who recollected the consecration did not want readers to imagine that Alfred had been selected as heir over his brothers. Nor did the writer seek to contrive a sense of amnesia among his readers and enchant them into believing that Alfred’s brothers had not ruled as Davis implies. What is more plausible is that what was intended above all was to link Alfred’s visit to Rome and the Pope with his status at the time of the Chronicles compilation, that of the undisputed ruler of his kindred within the demarcated territory he ruled over.

This does not mean that the meeting with the Pope ordained Alfred’s kingship. The encounter could have conferred a divine grace of sorts. The Pope had received Alfred and the record of this event precedes passages that detail the fight of the English against the heathen. For example, in the same entry that records the consecration.11 The Chronicles show an intent to unite the fate of the English with that of Christendom more broadly. Alfred is portrayed as a Christian soldier leading his people in a life and death struggle. He wages war for the security of his kindred and the salvation of the Christian faith within his kingdom. The record of consecration appears to be a device of smoke and mirrors used for broader dynastic, national, and religious reasons, rather than the comparably narrower and more individualistic motives that Davis seems to assign to Alfred.

The ‘positive error of fact’ Davis points to is one likely less concerned with Alfred’s right to the throne.12 The Pagan Vikings were the antithesis of the Christian English. After meeting the Pope in Rome, Alfred had gone on to lead his people successfully against their enemy, victory served to highlight the sanctity of the Christian faith and the role of the English in ensuring its sustenance….

To be continued.

For free pieces select the subscribe button

This has been the first piece in a two-part series. The next part will likely be published before the 1st of next month. In the coming weeks and months The Heritage Site will feature articles/essays on the Franklins, books and the kindle, the price of beer, and more. If you enjoyed this work on Alfred the Great then please hit the subscribe and share buttons.

Nicholas Brooks, Why is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle About Kings? Anglo Saxon England, 39, 43-70, 2010, 43

Simon Keynes, Manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in R. Gameson (Ed.), The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, 2011, 540

Michael Swanton, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, London, 2000, 64

R.H.C Davis, Alfred the Great, Propaganda and Truth, History, June 1971, Vol. 56, No. 187 (June 1971), pp. 169-182, 176

Barbara Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, London, 1990, 168-169

Swanton 63

For an analysis of Alfred’s translation programme please see Simon Keynes & Michael Lapidge, Alfred the Great, Asser’s Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources, Harmondsworth, 1983

Davis 176

Dorothy Whitelock, English Historical Documents, London, 1979, 533

Davis 176

Swanton 64

Davis 176