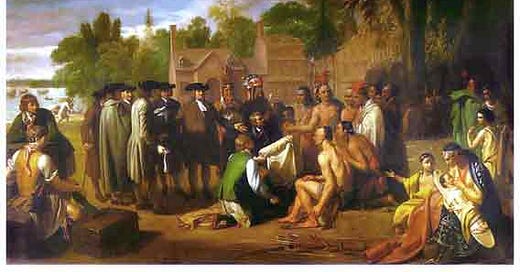

It was not with a detachment of armed men baring glittering swords or with soldiers standing behind ominously arrayed canons that William Penn greeted the Delaware Indians. He visited the natives to ratify a purchase of 45,000 acres of land that had been granted to him by Charles II in 1681. The land was a settlement for a debt of £16,000 that the king owed his father. Penn wrote a letter to the natives expressing his desire to live amicably with them as neighbours and friends. He acknowledged the injustices that had been done to them by European settlement in North America. He promised to satisfy any offences against the natives.1

‘Imagine the scene. In front of the Delaware with its peaceful and gentle banks waters; behind the native wilderness, owning for centuries no dominion but that of men wilder than itself.’ 2

Here in what would become Philadelphia, Penn reportedly closed his speech with the words, ‘‘We are now met on the broad pathway of good faith and goodwill so that no advantage is to be taken on either side, but all is to openness, brotherhood and love’’. 3 The colony bequeathed Penn was called Pennslyvania (Penn’s woods in Latin) and named after the younger Penn’s father by the king.

The Editor of the American Advocate of Peace lavishes praise on Penn, in an account laden with hagiographical flourishes, for pledging to appraise incursions against both planter and Indian as equal in stature, treating the natives as though they were his flesh and blood, deciding not to seek a paternal relationship with them, achieving treaties of amity and friendship with nineteen different tribes, urging natives not to drink alcohol, peacefully propounding Christianity, and providing instruction in religion via his funds, rather than by imposing faith at the point of the sword or gun.4 The Editor beamed, ‘well may the united voice of historians speak in praise of this treaty-ratified by no oath-and yet never broken, binding together in uninterrupted harmony the white and red inhabitants of Pennsylvania for more than seventy years.’5

The Quaker Penn was a spiritual man and paid the price for asserting his religiosity. He was tried at the Old Bailey for expressing his views.6 Acts such as The Corporation Act of 1661, and the Act of Uniformity of 1662, were passed following the Restoration. They tightened religious regulations and left substantial sections of English society, those who did not conform to the strictures of the established Church, in a state of disenfranchisement, through a ban on office holding, to note one example.

In this context, Penn sought to create a colony defined by religious toleration. From Penn's perspective, the ‘Inner Light’ that guided him and his fellow Quakers was not reserved for an elect few; it was in everyone. Massachusetts was a place of refuge for persecuted Puritans. Pennsylvania invited all believers in God to live side by side.7 Penn rejected compulsion in religion and he affirmed, ‘to do violence with the attempt of convincing the conscience, was to rob God's spirit of its office’.8

Throughout 1682-3, 4000 ships carrying 4000 settlers and ample supplies were sent to Pennsylvania.9 The colony was a magnet for religious dissidents. Quakers, Huguenots expelled from the France of Louis XIV, Mennonites from Holland and the Rhineland, and Lutherans and Calvinists from southwest Germany came to Pennsylvania for Penn's project of religious pluralism.10

German immigration heralded the founding of Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1683, although significant numbers of German immigrants would not arrive until the 1720s. J. H Elliot reasons that the frame of government drawn by Penn failed to create the well ordered and free society he envisioned, merchants and larger landowners, attracted by worldly allures over piety emerged, and Quakers and Anglicans feuded.11

After Penn passed away, his son Thomas Penn inherited the position of Proprietor of the colony in 1718, along with his brothers John and Richard. John died in 1746. Thomas continued as the Proprietor with Richard's son John until 1775. Thomas Penn asserted his independence from the Quakers and exercised quasi-feudal authority over the colony. The conduct of Thomas Penn and his Proprietary faction was the cause of much division in Pennsylvania. Their actions created many political opponents, including Benjamin Franklin and his son William.

During the Seven Years’ War, Thomas Penn was the colony executive. He controlled 40,000 miles of private land. Private buyers held 5,000 miles. They paid him rents in silver. Yearly revenues for these rents amounted to £10,000 at least. Thanks to Pennsylvania's royal charter, the Proprietors were allowed to make all laws with the consent of freemen and the approval of the king's Privy Council. In emergencies, Thomas Penn or his Lieutenant Governor could proclaim ordinances consistent with English law without the consent of freemen. In such scenarios, he had the authority to declare martial law and war. Further to this power, the royal charter gave the Proprietary authority control over all executive officials for the province's internal administration. 12

Thomas Penn is presented unfavourably in history, G.B Warden describes him as ‘undeniably a selfish man, and extremely jealous of his inherited political powers’.13 A common refrain heard among populations under the system of ‘‘liberal democracy,” is that politicians are “out of touch”. Those who believe in a political class being more attached to the public or “the people" ought to be thankful that they did not live under the governance of Thomas Penn. After 1740 he never set foot in his province ever again.14

More equitable forces were able to divest the Provincial Council of its power to veto bills passed by the Pennsylvania Assembly. However, the councillors achieved a similar effect to the veto by advising the Lieutenant Governor to appoint Proprietary men to relevant offices. Thomas Penn ensured that some Quakers and other moderate opponents were included in the Council. Compliant councillors could be rewarded with remunerative offices.15 Pennsylvanian politics was replete with cronyism, favouritism, and the affirmation of privileged interest. Office holders were linked by a mind-bending concatenation, the elite was united by marriage.16

Dr. Thomas Graeme, whose daughter Elizabeth courted William Franklin, served as the third Justice of the Supreme Court between 1731-1750. He was a director and the physician of Pennsylvania Hospital. He was close to the Proprietary faction, situated thoroughly in a marital managerial matrix aided by the institution of the Anglican Church.17 It is not hard to understand why he may have cast askance glances toward the younger Franklin. Along with his father, William opposed the hegemony of the Proprietors. However, William did become an Anglican; this may have done much to endear him to Elizabeth's family.

By this time, waves of immigration into the colony had made the Quakers a decreasing minority. Their dominance in the Assembly was threatened because of this. Pennsylvanian politics felt the strain inherent in Quaker pacifism and the need to raise funds for military purposes amid the exigencies of war.18

Until 1740 the Quakers had dominated the City Corporation of Philadelphia. Refusal to raise money and troops for King George's War led to their downfall, enabling the ascendancy of the Proprietary interest both politically and economically.19

In 1757, the Assembly appointed Benjamin Franklin as an agent to London to seek redress from the British government for a list of grievances against the Proprietors. The Penns' reluctance to pay any tax on their lands was a primary concern. This issue was salient given the chance of war. For this mission, William Franklin, who had served his father faithfully to this point, was the obvious candidate to work as his clerk in Britain.20

William had been pursuing a legal career, and a journey to London to complete his studies had long been in the offing. Now that he would be accompanying his father to the mother country in a working capacity, his first visit to Britain would involve official duties, study, and much more.

Before he left for London, William became engaged to Elizabeth Graeme. She accepted his proposal, provided William did not set himself against her father through factional politics. Under the pseudonym Humphrey Scourge, William had made political diatribes. Before leaving America, he had tried to marry Elizabeth, but she declined because this would anger her father. The pair agreed to stay betrothed until William's return.21

On the other side of the Atlantic, William intended to support his father and the Assembly. He wanted to do this without causing Elizabeth and her family angst; this would be a tough challenge.

Before we rejoin the Franklins’ in London, the next piece at The Heritage Site will feature a much neglected and overlooked but perhaps still important date on the English calendar.

J. H Elliot, Empires of the Atlantic World, 2006, 212: Editor, William Penn, American Advocate of Peace (1834-1836) Vol. 2, No.11 (December, 1836), pp.115-132, 119

Editor, William Penn, 121

Ibid 122

Ibid, 118, 123, 124

Ibid 123

Ibid 130

Elliot, 211

Editor, 129

Elliot, 212

Ibid

Ibid

G. B Warden, The Proprietary Group in Pennsylvania, 1754-1764, The William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 21, No. 3 (Jul., 1964), pp. 367-389, 367

Ibid 370

Ibid

Ibid 371

Ibid 373

Ibid

Ibid 375

Ibid 378, 380

Williard Sterne Randall, A Little Revenge: Benjamin Franklin and His Son, 1984, 114

Randall, 111, 68, 115