When we hear the word prejudice, our minds often turn to undue treatment dealt by one person to another or a claim of the same. A Google search of ‘prejudice’ returns the following headlines: Teen with dwarfism hopes success will end prejudice. Amid class prejudice and sensitivities over race, Rochdale’s abused girls were failed. AC Milan lights up San Siro against any form of racism, hate, and prejudice.1 In all these titles, prejudice is cast as a negative thing, but should this be the case? Can having, holding, and guarding a prejudice be morally justified?

The origins of the English word date from between 1250 and 1300. ‘Prejudice’ comes from Old French and the Latin praejudicium. Praejudicium refers to a ‘preliminary or previous judicial inquiry’. Prae meaning ‘in advance’, judicium meaning ‘judgement’.2 A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquitie, written in 1875, defines praejudicium as something that becomes an exemplum for the judiciary to follow. The term was used in the sense of a precedent and also in the sense of a preliminary inquiry and determination about something.3

A Google definition of prejudice is a ‘preconceived opinion that is not based on reason or actual experience’ and records an association with bias. Legal definitions note ‘harm or injury that results or may result from some action or judgement’ and causing ‘harm to some state of affairs’. The Cambridge Dictionary defines prejudice as ‘an unfair and unreasonable opinion or feeling, especially when formed without enough thought or knowledge’, and states, ‘Someone or something that prejudices you influences you unfairly so that you form an unreasonable opinion about something’, among other similar definitions. These meanings have decidedly negative connotations. With the word’s origins in mind, it would seem that a fair bit of violence is done to language when these contemporary definitions are accepted comprehensively.4

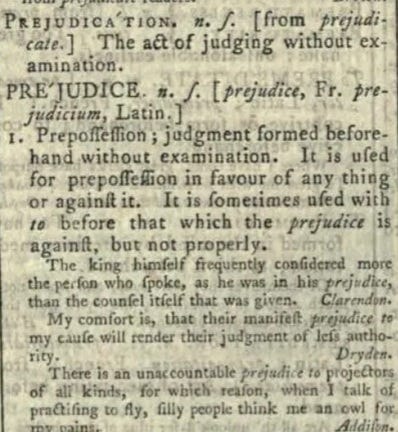

One man who saw the merits of prejudice was the British MP, writer, and political thinker Edmund Burke (1729–1797). Before exploring his illuminating use of the word, it is apt to acknowledge the description of ‘prejudice’ in a dictionary from Burke’s time titled A dictionary of the English language : in which the words are deduced from their originals, explained in their different meanings and authorised by the names of the writers in whose works they are found. The work was written by the famous lexicographer Samuel Johnson 1709-1784 and published in 1766. Its first definition of prejudice reads: ‘Prepossession, judgement formed beforehand without examination. It is used for prepossession in favour of anything or against it’. Its second definition is qualified: ‘Mischief; detriment; hurt; injury. This sense is only accidental or consequential; a bad thing being called a prejudice; only because prejudice is commonly a bad thing, and is not derived from the original or etymology of the word: it were therefore better to use it less’.5 Johnson’s first definition does not assign unfairness or injustice to the application of prejudice. It is morally neutral. The explanation for Johnson’s second definition has a caveat, advising the reader of its departure from the word’s origins and etymology. This definition comes from the word's use rather than vice versa. When he advises this definition be applied less often, he reveals his attempt to thwart the bastardisation of the word. Considering his advice today, it seems his words have often gone unheeded. When Johnson’s definition is understood and compared to the two online definitions discussed above, and when we consider the headlines at the top of this piece, we find that the word is now laden with cultural and moral baggage. Nowadays, the word seldom indicates the just application of prejudice.

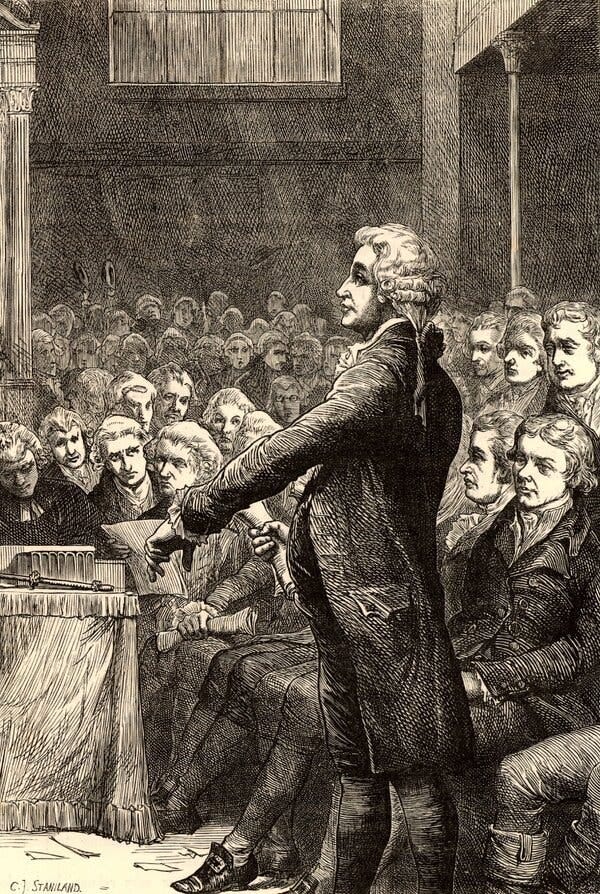

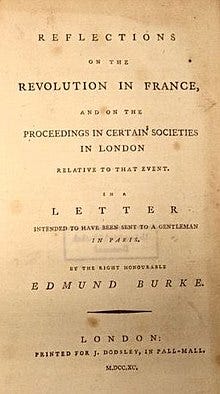

Burke was prominent in public life from 1765 to about 1795. He was important in the history of political theory. Before 1790, Burke was notable for his struggle against the king and ministers over financial matters, his efforts to secure commercial, religious, and parliamentary reform for Ireland, his plea for conciliation with the American colonies, and his advocacy for the punishment of those responsible for injustice in the government of India. His ‘Reflections on the Revolution in France’, published in 1790, opposed what he deemed to be the unjustifiable upheaval and tumult unleashed in that country. The work is also very concerned with events in Britain.6

Burke thought the French Revolution was a conspiracy by an intellectual and professional elite. Ambitious lawyers hungry for power, money lenders trying to take over church property, and a group of atheists seeking to curb the influence of religion on the French people were responsible. He called the insurrection the first ‘‘complete revolution”.7‘‘Never before this time was a set of literary men converted into a gang of robbers and assassins; never before did a den of bravoes and banditti assume the garb and tone of an academy of philosophers.”8

Burke lamented the evaporation of concern for past practices and institutions during the revolution. He believed that a natural aristocracy that values steadiness and social continuity should rule; this ruling group should be publicly spirited and serve the interests of the majority. He did not say an elite should occlude people from lower down the social scale, but he felt leadership should be a just reward for labour and successful experience. Various writers accept that Burke understood when change was necessary, and the term ‘progressive conservative’ has described him.9 The use of the word progressive in this context must not be confused with its employment today by remorseless degenerates who work to desecrate the best of our culture and society.

Burke believed abstract and metaphysical ideas could not adequately solve social and political problems, and he argued against thinkers who thought otherwise. He valued experience and context when dealing with complex matters. A people’s history is of great importance and aids future actions. Without ‘‘the collected reason of ages’’ principles could not become habits. Men’s habits would lose their course and become uncertain. The Reflections had one edition a month in England for the first twelve months of its publication, 30,000 copies sold before Burke’s death in 1797, and 16,000 copies of a French translation sold within a year of its release. ‘The Reflections’ became the Bible of the counter-revolutionaries of its day.’10 A passage from the work on the wisdom of prejudice is worth quoting in full, along with a preceding section to offer context:

‘In England we have not yet been completely embowelled of our natural entrails; we still feel within us, and we cherish and cultivate, those inbred sentiments which are the faithful guardians, the active monitors of our duty, the true supporters of all liberal and manly morals. We have not been drawn and trussed, in order that we may be filled, like stuffed birds in a museum, with chaff and rags, and paltry, blurred shreds of paper about the rights of man. We preserve the whole of our feelings still native and entire, unsophisticated by pedantry and infidelity. We have real hearts of flesh and blood beating in our bosoms. We fear God; we look up with awe to kings; with affection to parliaments; with duty to magistrates; with reverence to priests, and with respect to nobility. Why? Because when such ideas are brought before our minds, it is natural to be affected; because all other feelings are false and spurious, and tend to corrupt our minds, to vitiate our primary morals, to render us unfit for rational liberty.

You see, Sir, that in this enlightened age I am bold enough to confess, that we are generally men of untaught feelings; that instead of casting away all our old prejudices, we cherish them to a very considerable degree, and to more shame to ourselves, we cherish them because they are prejudices; and the longer they have lasted, and the more generally they have prevailed, the more we cherish them. We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason ; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations, and of ages. Many of our men of speculation, instead of exploding general prejudices, employ their sagacity to discover the latent wisdom which prevails in them. If they find what they seek, and they seldom fail, they think it more wise to continue the prejudice, with the reason involved, than to cast away the coat of prejudice, and to leave nothing but the naked reason; because prejudice, with its reason, has a motive to give action to that reason, and an affection which will give it permanence. Prejudice is of ready application in the emergency; it previously engages the mind in a steady course of wisdom and virtue, and does not leave the man hesitating in the moment of decision, sceptical, puzzled, and unresolved. Prejudice renders a man’s virtue his habit; and not a series of unconnected acts. Through just prejudice, his duty becomes a part of his nature.

Your literary men, and your politicians, and so do the whole clan of the enlightened among us, essentially differ in these points. They have no respect for the wisdom of the other; but they pay it off by a very full measure of confidence in their own. With them it is a sufficient motive to destroy an old scheme of things, because it is an old one. As to the new, they are in no sort of fear with regard to the duration of a building run up in haste; because duration is no object to those who think little or nothing has been done before their time, and who place all their hopes in discovery.’11

Burke cherished the English regard for inherited sentiments. When he says that the English ‘have not been drawn and trussed’ to be filled with ‘chaff and rags, and paltry, blurred shreds of paper about the rights of man’, he positions himself forcefully against the rash repudiation of tradition for abstract ideas. His reverence for God, monarchy, parliament, magistrates, and nobility is given voice in the context of an assault on the same in France.

Burke proudly declares an affection for prejudices, especially those long lasting ones. He favours drawing from a repository of thought over deferring to the view of a lone person. When noting a smallness in any individual’s stock of reason, he appeals to humility and prudence; this reference, like others in the passage, is relevant to today’s moral and cultural debates. Employing' sagacity’ in discovering the ‘latent wisdom’ prevailing in prejudices may be to our avail. Anyone who has ever sat in an undergraduate or postgraduate history seminar may have encountered the invocation of uncomplimentary cultural references made in the past. Such invocations present European travellers during the imperial epoch as having narrow and immoral views. The mere use of terms like ‘‘savage’’ to describe members of an out-group is enough to invite scorn and recourse to the liberal shibboleth of “racism”. Instead of accepting the opinion of that student or that lecturer, what would happen if we were to delve into the historical record and understand how and why what one might term prejudice developed? Some may not like what they find and discover that maybe some prejudice is understandable. A Burkean approach commands those who condemn an opinion or prejudice as immoral or unjust to prove their point before ‘the coat of prejudice’ is tossed aside; this allows us to guard against the elevation of absurdities to the rank of truth.

Burke’s view that ‘prejudice, with its reason, has a motive to give action to that reason’ invites the consideration of instances where prejudice is justified. We may forgive those who read R.H. Bacon’s Benin: The City of Blood in 1897 for developing prejudice against the people of Benin and their culture; the British saw Benin as a cruel and tyrannical place. Bacon was the intelligence officer for a British expedition in 1897. He said, ‘‘Benin’s history is one long record of savagery of the most debased kind." ‘Bacon and his colleagues discovered several compounds for human sacrifice. In one case, ‘the altar was deluged in blood, the smell of which was too overpowering for many of us.’’ Indeed, ‘‘the one lasting remembrance of Benin in my mind is its smells. Crucifixions, human sacrifices, and every horror the eye could get accustomed to’’. ‘Then there were the burial pits: ‘And these pits…out of one a Jakri (Itsekiri) boy was pulled with drag-ropes from under several corpses; he said he had been in five days’. ‘Blood was everywhere; smeared over bronzes, ivory, and even the walls’. And there was also the ‘crucifixion tree with a double crucifixion on it, the two poor wretches stretched out facing the west, with their arms bound together in the middle…At the base were skulls and bones, literally strewn about…Down the avenue to the right was a tree with nineteen skulls…and down every main road were two or more human sacrifices.’’12 Bacon’s account was corroborated.

Without having a reason to distrust Bacon, a European traveller who read his work would have kept it in mind ahead of any inter-cultural encounter in Benin or nearby. It might have been unreasonable for an explorer to assume that everyone from Benin would engage in human sacrifice, but caution and suspicion would have been justified.

The descriptions penned by Bacon and the like may shock readers today, but in the past Europeans often wrote and spoke as they saw. They did not have to filter every thought and opinion to serve politically correct imperatives. They could be honest. As for European views of other cultures more broadly, these can be debated. However, the condemnation of Europeans for aversion to aspects of disparate cultures cannot be allowed to stand.

Burke’s words on the destruction of an old scheme of things on account of its age evoke the arrogance with which our ancestors are derided and judged according to the assumptions of the present. Historical figures are put under a contemporary lens and appraised anachronistically according to criteria devised in very recent times. Ahistorical practices deprive learners of constructive conversations about the key figures and events that have shaped the world. In detecting the disregard by those who deprecate older ways and achievements, Burke appeals again to humility and caution. These traits may be useful when judging the past. We may glean more by considering a society in the global context of its time.

In Britain today, we often hear the term ‘modern Britain’. There is an emphasis on ‘a modern monarchy’, ‘modern attitudes’, and a range of institutions and organisations needing to reflect ‘modern Britain’. When someone asserts a need for modernisation, justification for such a scheme is routinely absent. Why should we assign any value to anything solely because it is modern? Especially if much of this represents what we did not solicit or consent to. Burke invites us to consider the merits of what has kept things on a steady and familiar course. Why should we not maintain ‘the whole of our feelings still native and entire’ and value what was and what still is?

There are several ways in which positive prejudice may benefit us today. A traditional Western family structure, marriage, a confident national culture, and Christian ethics have benefited European peoples. Prejudice in favour of the same may be of benefit again. One only has to observe the fraught and dysphoric condition of many people today, the adverse consequences of single parenthood, rampant moral decay, narcissism, and the assault on the British national character to realise this.

Burke’s thoughts on prejudice in the context of the French Revolution resonate today. His view of successful experience as a prerequisite for an elevation of status stands in diametrical opposition to those who demand the aggrandisement of people from this or that client group. His preference for inherited wisdom over abstract ideas invites us to consider the past and any significant changes with care and fairness. Far from being something we should automatically discard, our prejudices can be of great help.

acmilan.com, AC Milan lights up San Siro against any form of racism, hate, and prejudice, AC Milan, 27/01/2024, https://www.acmilan.com/en/news/articles/club/2024-01-27/ac-milan-lights-up-san-siro-against-any-form-of-racism-hate-and-prejudice, accessed: 3/3/24: Kenan Malik, Amid class prejudice and sensitivities over race, Rochdale’s abused girls were failed, The Guardian, 21/1/24, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/jan/21/amid-class-prejudice-and-sensitivities-over-race-rochdales-abused-girls-were-failed, accessed: 3/3/24: BBC, Teen with dwarfism hopes success will end prejudice, 6/3/2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-england-bristol-43300124, accessed 3/3/24.

Dictionary.com, dictionary.com/prejudice, accessed: 3/3/24: Oxford Learner Dictionaries, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/prejudice_2, accessed: 3/3/24

George Long, Praejudicium, in A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, 1875, from The University of Chicago, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Praejudicium.html, accessed: 3/3/24

Google, search: ‘prejudice meaning’ accessed: 3/3/24: Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/prejudice, accessed: 3/3/24

Samuel Johnson, A dictionary of the English language : in which the words are deduced from their originals, explained in their different meanings and authorised by the names of the writers in whose works they are found, 1766, 378, from Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofengl02johnuoft/page/n377/mode/2up?view=theater, accessed: 3/2/24

Charles William Parkin, Edmund Burke, British philosopher and statesman, Britannica, last updated 20/2/24, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edmund-Burke-British-philosopher-and-statesman, accessed: 3/3/24

Louis Gottschalk, Reflections on Burke’s ‘Reflections on the French Revolution’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 100, No.5 (Oct 15, 1956), 417-426

Ibid 426

Richard Glen Eaves, Edmund Burke: His enduring influence on political thought, Journal of Thought, Vol.14, No.2 (April 1979), 123-124, 128

Gottschalk, 419, 428

Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France’, 1790, published in Penguin Classics in 1986, 182-184

Nigel Biggar, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, 2023, 233-234

I'm embarrassed to say I've never read Burke's 'Reflections on the Revolution in France.' You've prodded me into action!