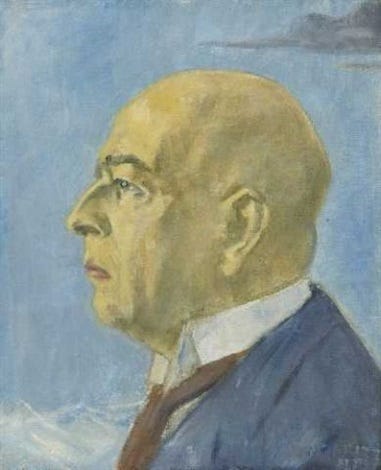

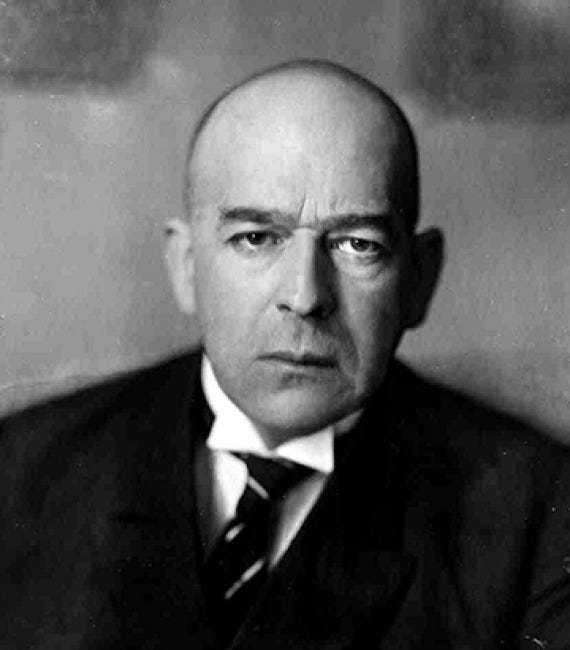

Faustian Arts As Told By Oswald Spengler

Music and Plastic in Oswald Spengler's Decline of The West, Volume 1, Form and Actuality

According to Oswald Spengler, cultures are akin to organisms. They are born, grow, develop, ripen, decline, and die. In The Decline of the West, Volume I, Form and Actuality, 1918, Spengler maps the history of cultures with spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Our Western culture, or our Faustian culture as Spengler calls it, began in the tenth century. Our spring, the Gothic period, occurs from 900-1500. Summer, the Baroque epoch, from 1500-1684. Autumn, the Enlightenment, from 1685-1788. Spengler’s model places our age in the winter/civilisation phase. We entered this time around 1789. 1

The oppositional forms of the Classical and Western cultures are omnipresent features in The Decline. Two chapters in the book are called Music and Plastic; they focus heavily on the artistic differences between the Classical and Western worlds. Each of the two chapters has a subtitle. One is The Arts of Form; the other is Act and Portrait. This article will traverse these chapters. It will present Spengler’s view of the Faustian ‘primary symbol' and its impact on the arts. It will refer to the symbol of the Classical culture too. The piece will note some of Spengler’s most fascinating insights and convey some understanding of what Western culture meant to him.

Spengler reasons that a unique primary symbol exists in every culture. Cultural uniqueness manifests in many aspects. One example of the oppositional nature of the Classical and Faustian cultures is in painting. Classical culture conceived of painting in plastic; Faustian painting became musical. For the former, art was a ‘static of things’. For the latter, it is a ‘dynamic of space’. Spengler asserts that this binary reveals the opposition of Classical and Faustian ‘world feeling’. 2 The dissimilarity is not a result of a transition from one thing to another. Western culture did not grow out of Classical culture. The cultures are antithetical and have alternate metaphysical orders.

Spengler said the sixteenth century was the ‘decisive epochal turn’ for Western painting. Here, it becomes picturesque and infinity-seeking. The hitherto casually put-in background increases in importance. The horizon becomes characteristically Faustian. The aptness of a horizon to a landscape is self-evident to us, but it is not present in ‘Egyptian relief or in Byzantine mosaic or vase paintings and frescoes of the Classical age’. Spengler detected that the development of the horizon in Western art is unparalleled in any other culture.3

The technique of oils became the basis of an art that strives to conquer space and dissolve things in space. ‘The art of the brush claims kinship with the style of cantata and madrigal.’ The colours of Western painting became tones.4 Spengler elaborates on the intimate relation of Faustian painting and music. ‘The distance separating two kinds of painting can be infinitely greater than that separating a painting and a piece of music from the same period. Compared to a statue of Myron, the art of a Poussin landscape is the same as that of a contemporary chamber cantata; that of Rembrandt as that of the organ works of Buxtehude, Pachelbell and Bach; that of Guardi as that of the Mozart opera-the inner form language is so nearly identical that the difference between optical and acoustic means is negligible.’5 The idea of a piece of music and a painting being more similar to each other than two paintings or two pieces of music may seem odd at first. Spengler saw in Faustian painting an ability to penetrate great inward and outward depths and a desire to reach out across infinite distances. In Faustian music, he discerned the same. The Greek ‘felt the marble with his eye, and the thick tones of an aulos moved him almost corporeally. For him, eye and ear are the receivers of the whole impression that he wished to receive. But for us this had ceased to be true even at the age of Gothic’. The fugues of Bach and the last quartets of Beethoven take us ‘behind the sensuous impressions’. Then ‘the fullness and depth of the work begins to be present to us, and it is only mediately-through the images of blond, brown, dusky and golden colours, of sunsets and distant ranked mountain summits, of storms and spring landscapes, of foundered cities and strange faces which harmony conjures up for us-that it tells us something of itself. It is not an accident that Beethoven wrote his last works when he was deaf-deafness merely released him from the last fetters. For this music, sight and hearing equally are bridges into the soul and nothing more’.6 Spengler saw Impressionism as an art that ‘penetrates the body, breaks the spell of its material bounding surfaces and sacrifices it to the majesty of space'. Baroque music did the same.7

Western man’s drive to ascend to ever greater heights and to go beyond ever greater distances was revealed in the arts. Spengler detects this drive in Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1606-1669, who Spengler says never painted a picture with a foreground.

Rembrandt’s Landscape with a Coach assumes a far-reaching perspective. One can also see in this image what Spengler may have perceived as an absence of foreground. The coach and horse and the buildings to the left are in darker shade. The horizon, landscape, and sky subordinate the other elements of the painting. The changing heights of the ground accentuate its vastness and depth.

Spengler asks, ‘To fly, to free one’s self from earth, to lose one’s self in the expanse of the universe- is not this ambition Faustian in the highest degree? Is it not in fact the fulfilment of our dreams?’ He writes elegantly on the Christian legend in Western art, painting fine brush strokes on the mind of the reader: ‘All the pictured ascents into heaven and falls into hell, the divine figures floating above the clouds, the blissful detachment of angels and saints, the insistent emphasis upon freedom from earth’s heaviness, are emblems of soul-flight, peculiar to the art of the Faustian, utterly remote from that of the Byzantine.’8 Conversely, Classical art does not concern itself with horizons and clouds.9 Spengler finds that Classical painting, in its strictest style, limits its palette to yellow, red, black, and white. ‘Blue and green are the colours of heavens, sea, fruitful plain’. They disembody and evoke expanse, distance, and boundlessness. ‘For this reason they were kept out of the frescoes of Polygnotus. And for this reason also, an ‘‘infinitesimal” blue-to-green is the space creating element throughout the history of our perspective oil painting, from the Venetians right into the nineteenth century.’10

Spengler discerns an artistic Western exclusivity in opposition to popular Classical art. ‘Yellow and red are the popular colours, the colours of the crowd, of children, of women, of savages,’ and they are the colours of ‘noisy hearty market days and holidays’. Blue and green are the ‘Faustian monotheistic colours’ They are colours of direction that relate to a past, present, future, and destiny.11 ‘The whole of our great oil painting, from Leonardo to the end of the 18th Century, is not meant for the bright light of day.’ It is a studio art. Classical art was public.

The use of blue and green, ‘with their powers of dissolving the near and creating the far, would have been a challenge to the absolutism of the foreground’ and ‘very meaning and intent of Apollinian art’, and it would have opposed the Classical world feeling epitomised by the figure of the body.12 Spengler detects that the Classical fresco painting is tied to the wall whereas the Western oil painting emerges on canvas, board or another table, ‘free from the limitations of place’.13

The physiognomic character of Western art distinguishes it from Classical art. ‘Western portraiture is biography’ and ‘historical confession’. He invokes Holbein, Titian, Rembrandt, Goya. ‘The meaning and representation of the human phenomenon remains entirely in the head’ and not in the body.

The ‘character of the Renaissance as a protest against the Faustian spirit’ betrays itself. Spengler cites Giovanni Bellini’s Doge, ‘the first great oil portrait’ as one example. Portraiture is too Faustian a symbol. There was no genuine Renaissance, no real recrudescence of the Classical, and the movement failed to make good on its ‘anti-Gothic principle’.14 It could not repress the primary Faustian symbol.15 Spengler judges Leonardo’s Adoration of the Magi as the ‘grandest piece of artistic daring in the Renaissance’. It transcends ‘all optical measures’ and ‘pushes fearlessly on to challenge eternal space; everything bodily floats like the planets in the Copernican system and the tones of a Bach organ-fugue in the dimness of old churches’. Spengler notes the achievement in light of the technical possibilities of its time.16 The work carefully penetrates space with its impressive grouping of bodies.

Faustian art after 1800 is in the Civilization phase. The transcendence that deployed its full forces from 1550 is no more.17 Spengler registers this decline with the following observation: 'Rembrandt's mighty landscapes lie essentially in the universe, Manet's near a railway station'. Megalopolitans (the people of the large modern cities) treat landscapes empirically and scientifically.18 Head overcomes heart. Knowledge defeats faith. Rationalism and science reign in Civilization, and no new great art emerges.

Spengler finds an abandonment of proportion in the art of Civilization. A taste for the gigantic manifests. 'Here size is not, as in the Gothic and the Pyramid styles, the expression of inward greatness, but the dissimulation of its absence.’ A 'swaggering in specious dimensions is common to all nascent Civilisations'.19 Spengler offers architectural examples from Greece and Rome. He then refers to the 'American skyscraper of today'. The skyscraper reflects the absence of beauty and positive cultural meaning in contemporary buildings. In London in 2020, the structure pictured above, by Heather Phillipson, occupied the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. The oversized ice cream, revoltingly met by a fly, with a cherry on top, is called ‘The End’. It stood as if to trivialise the important landmarks and buildings around it and mark an end to the aesthetic decency of the area. Ekow Eshun, then chairman of the Fourth Plinth commissioning group said, “It expresses something of the fraught times that we're living through, while also standing in conversation with the artistic and social history of Trafalgar Square.”20 Indeed, it expresses something of our fraught times, most pointedly the sorry state of artistic standards. Rather than ‘‘standing in conversation”, if anything, it appears to operate more in the way of someone hurling vitriolic abuse into the street. One wonders what this incongruous absurdity offers, except an understanding of today's cultural degeneracy.

Happy New Year.

For more on Oswald Spengler, see my piece on the introduction to The Decline.

A Discourse On Oswald Spengler's Decline Of The West

‘I see, in place of that empty figment of one linear history which can only be kept up by shutting one’s eyes to the overwhelming multitude of the facts, the drama of a multitude of mighty cultures, each springing with primitive strength from the soil of a mother region to which it remains firmly bound throughout its whole life cycle; each stamping its …

1 Neema Parvini, The Prophets of Doom, 2023, 79

2 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, Volume I, Form and Actuality, authorised translation with notes by Charles Francis Atkinson, Alfred A Knoof, New York, 1928, 220, 227

3 Ibid 239

4 Ibid

5 Ibid 220

6 Ibid

7 Ibid 286

8 Ibid 279

9 Ibid 239

10 Ibid 245

11 Ibid 246

12 Ibid 247

13 Ibid 266

14 Ibid 263, 270

15 Ibid 279, 280

16 Ibid 277

17 Ibid 288, 282

18 Ibid 289

19 Ibid 291

20 Lizzie Edmonds, ‘The End: Heather Phillipson's 'dystopian' cherry-topped cream swirl lands on Fourth Plinth’ The Standard, 30/7/2020, accessed: 28/12/23

Very nice piece. Spengler's understanding of seasonal phases of civilisation and the human spirit are very much aligned to the World of Tradition and in particular, the dharmic understanding of the yugas.