A Discourse On Oswald Spengler's Decline Of The West

Volume I Form and Actuality: Some notes on the Introduction

‘I see, in place of that empty figment of one linear history which can only be kept up by shutting one’s eyes to the overwhelming multitude of the facts, the drama of a multitude of mighty cultures, each springing with primitive strength from the soil of a mother region to which it remains firmly bound throughout its whole life cycle; each stamping its material, its mankind, in its own image; each having its own idea, its own passions, its own life, will and feeling, its own death. Each culture has its own new possibilities of self-expression which arise, ripen, decay, and never return.’1

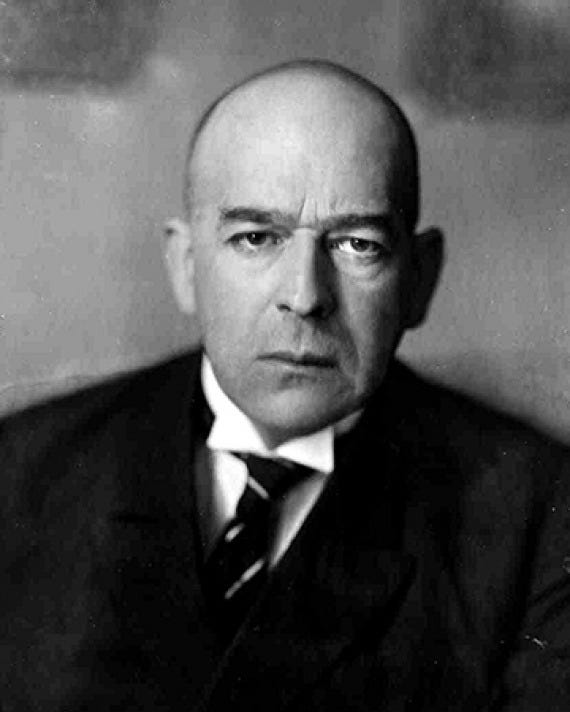

In The Decline of the West, (hereafter The Decline) Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) criticises the historical research of his day and offers an organic and cyclical interpretation of world history that allows us to understand the past and see into the future. He opposes his contemporaries for their Eurocentric historical approach. Spengler suggests a broader view that does not revolve around any particular location or culture.

Spengler was born in the Duchy of Brunswick in 1880 to Protestant parents. His father worked as a senior postal secretary, and this side of his family were traditionally mining engineers and metallurgical inspectors. His mother came from a line of ballet dancers. After excelling in Greek, Mathematics, and the Sciences at school, Spengler attended universities in Munich, Berlin, and Halle.

In 1904, three years after his father died, Spengler achieved his PhD at Halle. Then he worked as a schoolmaster. When his mother died in 1910, he lived on a modest inheritance as a private scholar. Spengler was exempt from military service in World War I due to having a weak heart. 1918 saw the release of the first volume of The Decline and the second volume came in 1922. Spengler died of a heart attack on 8 May 1936, in Munich, three weeks before his fifty-sixth birthday.

Spengler attacks the ‘empty figment’ of one linear history for masking a story of cultures that each have a life cycle where their image, ideas, passion, life, and feeling become before an inevitable death. From his purview, the West of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was at a stage evident in every culture to have ripened to its limit.2

When the great architectural and artistic forms within a culture cease to develop and flourish, a phase of cultural decline that Spengler calls 'civilisation' is manifest. Civilisation is the winter phase of culture. Spengler’s use of the word differs from our understanding of it. People today do not intend to evoke a culture in its winter when using the term. In civilisation, culture ceases to ascend and imitates prior forms. The vitality and power of an efflorescence in a culture's spring give it bright rays in summer before the inevitable onset of senescence.

Spengler states Classical culture came to civilization in the fourth century. Western culture saw it in the nineteenth. This distinction may surprise many who see the West as heir to a kindred Classical culture. To Spengler, these cultures differ markedly and each possess a distinct soul and feeling. Further along, this piece will pay some attention to the intrinsic peculiarity of cultures that Spengler sees.3 In civilisation, the city is the major decision-making locus. The older landscape of culture becomes merely provincial, and energies move to the dominant metropole.4 The world city and the province are what Spengler terms ‘the two basic ideas of every civilisation.’5

‘In place of a type-true people, born of and grown on the soil, there is a new sort of nomad, cohering unstably in fluid masses, the parasitical city dweller, traditionless, utterly matter of fact, religionless, clever, unfruitful, deeply contemptuous of the countryman and especially that highest form of countrymen, the country gentleman. This is a very great stride towards the inorganic, towards the end-what does it signify? France and England have already taken the step and Germany is beginning to do so. After Syracuse, Athens, and Alexandria comes Rome. After Madrid, Paris, London come Berlin and New York. It is the destiny of whole regions that lie outside of the radiation-circle of one of these cities-of old Crete and Macedon and today the Scandanavian North- to become ‘’provinces’’.6

Spengler's words will resonate with many who know London. We can detect a loose analogy between what he describes and the divisions in society today. He evokes the disdain our “liberal-elite” have for people who do not share their values and sensibility. The “little Englander” receives particular abuse.

In London, transient masses extract what they can financially, socially, and sensuously. National traditions are not of high importance to the urbanite. Many slavishly accept a life bereft of transcendence. Global man is booted, suited, and spiritless. In the City of London, there are many churches. These buildings do not play a meaningful role in the lives of most who work in the skyscrapers towering above them. The spreadsheet has usurped the soul. Every day millions bovinely adhere to imperatives that extol economic growth, consumption, and material possessions over anything of greater significance.

The city dweller passes through the university and parrots the values of so-called “liberal democracy" handed to him by the same institution to have indebted him to this cause. He then moves into a workplace that will confirm the biases of the education system. Conformity enables him to afford an exorbitantly priced room or apartment in a nondescript tower block. He has no idea who the hundreds of residents above and beneath him are. However, he manages to imbue himself with a sense of virtue. He willingly receives the embrace of government dictates. He feels he is right. This feeling often gives rise to a conceit, leading him to loathe the man who does not regard himself as a ‘‘citizen of the world’’.

The countryman is synonymous with rurality, place, dwelling in the land, patriotism, and continuity. What applies to him may be said to apply to others who do not happily digest the culture of the city dweller. The former does not feel the need to erupt with near-erotic glee like the “liberal” does when gushing over the “vibrant" variety of restaurants in London. Instead, he embraces his own national identity. If he is English, a meal enjoyed inside a pub beside a crackling fire situated on a country lane will often suffice. Nothing will make him agree to the retreat of the said lane for new housing developments that will erode his sense of what home means to him. He loves living in a less crowded place where he knows most people. The city dweller refuses to appreciate this preference and dismisses it as retrograde and bygone.

The divide between the city dweller and the countryman loosely relates to the dispute over British membership in the EU. Some lean toward cosmopolitanism and change, and some favour continuity and tradition.

Those who reason that the British government privilege London and the southeast over the rest of the country are likely to see parallels between the contempt described by Spengler and the attitudes of metropolitan types to more provincial areas today. Such a dynamic was a factor in northern constituencies voting to leave the EU in 2016. In some ways, Brexit was a rebellion against globalisation and much of what the capital represents.

The split between London and smaller cities and the provinces may be just as mental as physical. Not everybody in a metropolis is spiritless and careless of tradition, and in other regions, you will find people manifesting the traits of Spengler’s city dweller.

When affirming his scientific view of human history, Spengler states that his own time: ‘represents a transitional phase which occurs with certainty under particular conditions, there are perfectly well-defined states (such as have occurred more than once in the history of the past) later than the present-day state of West Europe, and therefore the future of the West is not a limitless tending upwards and onwards for all time towards our present ideals, but a single phenomenon of history, strictly limited and defined as to form and duration, which covers a few centuries and can be viewed and, in essentials, calculated from available precedents.’7

Spengler invites his reader to attain a high plain of contemplation to understand world history: ‘and already trained to regard world-historical evolution as an organic unit seen backwards from our standpoint in the present, we are enabled by its aid to follow the broad lines into the future-a privilege of dream calculation till now permitted only to the physicist.’8 Spengler asserts that his reader will learn to find not only what can happen but 'what with the unalterable necessity of destiny and irrespective of personal ideals, hopes, or desires, will happen.'9

Spengler characterises the Western man as uncertain, groping, and feeling his way about. However, armed with the knowledge that The Decline will impart, we will see our own lives in relation to history’s culture-scheme.10

Spengler encourages channelling Western energies to practical feats in engineering and politics; this is of more value than endeavours entailing lyrics and the paintbrush. For this philosopher of history: ‘the depths and refinement of mathematical and physical theories are a joy; by comparison, the aesthete and physiologist are fumblers. I would sooner have the fine mind-begotten forms of a fast steamer, a steel structure, a precision lathe, the subtlety and elegance of many chemical and optical processes, than all the pickings and stealings of present-day ‘’arts and crafts,’’ architecture and painting included. I prefer one Roman aqueduct to all Roman temples and statues. I love the Colosseum and the giant vault of the Palatine, for they display for me today in the brown massiveness of their brick construction the real Rome and the grand practical sense of her engineers, but it is a matter of indifference to me whether the empty and pretentious marblery of the Caesars-their rows of statuary, their friezes, their overloaded architraves-is preserved or not.’11

Many inventors, diplomats, and financiers are superior to the type that engages in a variant of some philosophy. Spengler detects that Romans of intellectual eminence led armies, organised provinces, and built cities and roads.12 He favoured practical actors who gave tangible results over those who merely theorised and led cloistered lives.

Spengler presages a critique of Emmanuel Kant by disapproving of those who readily systematise knowledge. We must judge a thinker by his eye for the facts of his time and not by awareness of definitions and analysis. Kant put the utmost possibilities of systematic philosophy to its end, as far as the Western soul is concerned.13 Following this came a more practical, irreligious, and social-ethical philosophy. After Kant came Schopenhauer, and we can find similar sequences in other cultures.

After trying to slam the caskets of both Western systematic and ethical philosophy shut, Spengler tells us, a ‘third possibility, corresponding to the Classical Scepticism, still remains to the soul-world of the present-day West, and it can be brought to light by the hitherto unknown methods of historical morphology'.14 Historical morphology is intrinsic to The Decline. We should not apply principles of causality, law, and system, that is ‘the structure of rigid being-to the picture of happenings'.15

Spengler states that some assumed we should study human culture the same way as other scientific things. No one enquired why certain symbols appeared when they did and why they were present for a given time. Historians have noted coincidences between places and figures. Spengler saw such historical similarities as a destiny-problem and urged the serious treatment of this matter with a scientifically regulated physiognomic to find out what was at work. The timing of events is never irrelevant. A phenomenon is not only an object but a symbol, be it something small or large in scale.16

Although the title of The Decline suggests a work with an explicit focus on Europe and wherever Europeans have created societies, Spengler has broader concerns. His cultural comparisons compel. The focus of Classical culture was decidedly on the present over the past and future. What the Greeks called Kosmos was an image of a world that is complete and not continuous, although they were aware of 'the strict chronology of and almanac-reckoning of the Babylonians and especially the Egyptians'.17 The orientation of Classical history also slants to the present; ‘what is absolutely hidden from Thucydides is perspective, the power of surveying the history of centuries, that which for us implicit in the very concept of a historian’.18 Conversely, 'The Egyptian soul, conspicuously historical in its texture and impelled with primitive passion towards the infinite, perceived past and future as its whole world,’ and the present ‘appeared to him simply as the narrow common frontier of two immeasurable stretches.’19 The Egyptian care for the future expresses itself with the mummy and the immortalisation of the dead man through portrait-statuettes, to take one example. ‘Today, pathetic symbols of the will to endure, the bodies of the great Pharaohs lie in our museums, their faces still recogniseable.’ In opposition, ‘we meet at the threshold of the Classical Culture, the custom, typifying the ease with which it could forget every piece of its inward and outward past, of burning the dead.'20

We will discover more in future posts on Spengler's magnum opus.

Hit the subscribe button to receive free pieces via email.

HERITAGE, HISTORY, CULTURE

References

Oswald Spengler, The Decline of West, Volume I, Form, and Actuality, authorised translation with notes by Charles Francis Atkinson, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 1928, 21

Ibid 39

Ibid

Ibid 32

Ibid

Ibid 32-33

Ibid 39

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid 40-41

Ibid 43-44

Ibid 44

Ibid 45

Ibid 45

Ibid 49

Ibid

Ibid 9

Ibid 10

Ibid 12

Ibid 13

Oswald Spengler - an intellectual life - Engelsberg ideas

Oswald Spengler, 1880-1936 (historyguide.org)

Oswald Spengler | Biography, Books, & Facts | Britannica