It was a pleasant interaction less common in London than outside of it. When looking at an elegant medieval structure and absorbing serene surroundings, it is clear to an elderly lady moving towards me that I am not a local. She notes the inscription by my feet and directs me towards other words marking the path around the building. I say thank you, wish her well and begin to walk. Caution and a healthy sense of suspicion are advisory when strangers approach in our big cities, even if they are holding a Zimmer frame. The imminence of crime there can militate against openness to those unfamiliar. Cultural incoherence pervades places like London and often leaves people feeling on guard. Thankfully, I am not in a major city. Horsham, West Sussex is my choice for a break from things. I got here early, comfortable cool air and a sun persistently trying to make its presence felt accompany my morning stroll. Soon after stepping off the train, I felt grateful for Horsham's visual and auditory character. The town centre is pleasantly laid out with agreeable buildings and walkways. There is no foreign signage or much evidence of symbols that counter-signal England. No alien noise cuts through the air obtrusively in denial of an English sense of home. Instead, the sounds are largely pleasant and measured. Walking along a path and reading uplifting biblical inscriptions etched onto the floor, I savour the calm. Beyond the gravestones at the back of the church, the sound of a rushing stream combines with the sight of green grass and plants. The setting beckons those searching for peace. Benches are near, and I take a seat.

I read restfully for a good hour or so without any interruption. Quiet, foliage, the sound of flowing water, and the written word blend wonderfully.

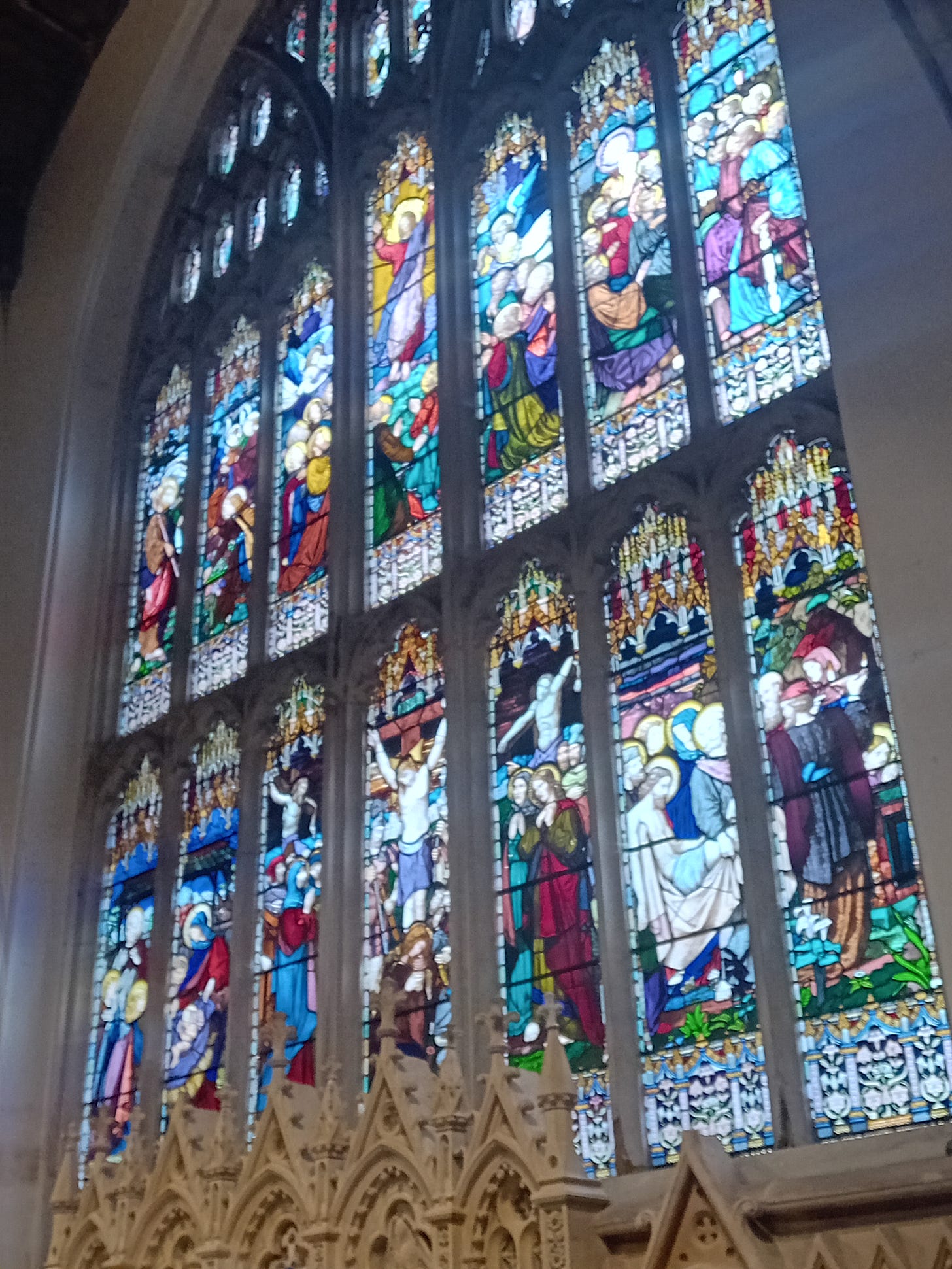

Then I enter St Mary's Church, founded in 1247, and look around. We might assuage many of our current ills with the help of a Christian revival. The press has reported on a rise in church attendance over the Easter weekend, and data from the Bible Society suggests this enthusiasm may not be fleeting. In 2018, 4% of 18- to 24-year-olds they surveyed reported attending church monthly, compared with 16% in 2024. For men, this increased from 4% to 21%, and, for women, from 3% to 12%.1 Disenchantment arising from a secular materialism that cannot answer questions of meaning and belonging accounts for this in some ways. Given the current cultural decline and the prominence of Islam in society, it is natural that people will turn to Christianity. It was the basis of our society and culture during Britain’s most stable and successful periods. The decline of British Christianity created a spiritual lacuna. An assessment of a spiritually sterile society may be persuading many to turn to Christ.

Soon after exiting St Mary's, I enjoy a coffee at a nearby shop. The place has English staff. These are people who liberals often tell us do not want to work in such jobs. This experience brought to mind an infamous segment of BBC Question Time from some years ago featuring a cretinous individual appealing to the audience to support mass migration lest she fail to be served in Pret a Manger. One wonders if people operating at such a mentally attenuated level are too far gone. Although the shop is busy and there is chatter, I can concentrate on my work. Noise levels are reasonable, and the room is full of people speaking English. But this alone does not account for the positive experience. The language is complemented by the characteristically English cadence I hear when those near me speak it. The pleasant homogeneity is not punctuated with anything else. Nothing is sonorous or grating. No reprobates shout into devices that play aloud. Serenity of this kind is increasingly rare across much of Britain. This is an English space. It is an example of our temperament, manners, and disposition. When questions of identity and belonging arise, there is often recourse to political traditions and values; the latter invariably fails to leave the realm of the abstract and reify anything. Any development lessening the likelihood of the experience I describe is something we ought to vehemently oppose. The simple things we are losing are important aspects of our way of life and should not be forgotten amid the usual narratives.

After making some progress on an ongoing project, I view some pubs. Ye Olde Stout House and The Bear are within a few minutes of each other, and both have an inviting aesthetic that includes distinctive frontages. I prefer the darker interior of the former pub over the lighter contemporary flooring and panelling in the latter. The Bear’s fittings do not provide the sense of being lived in that the greatest alehouses possess. Nonetheless, it is pleasant and complemented by an intimate space outback. The Black Jug is a warm and inviting venue. Inside, you will see the wooden panelling of a traditional pub. The old pictures and clay pipes on display are suitable features.

A good documentary would observe life of the kind prevailing in Horsham. Should this come to pass, the viewer would see something worth fighting for.

All subscriptions, likes and shares are very much appreciated.

Sebastian Morello, This Easter, the Church Is Rising from the Grave, The European Conservative, 18/4/25, https://europeanconservative.com/articles/commentary/this-easter-the-church-is-rising-from-the-grave/, accessed: 25/4/25

Beautiful description of an England that has almost disappeared, thanks.

The Sunday bells of Horsham call,

Across the roofs of tilting hall.

Grey flint and redbrick blend and glow,

Beneath the April rains that blow;

And down the narrow cobbled street,

The ghost of Georgian footsteps beat.

Ah, Horsham! Lovely place, I know the area well. London feels like an alien country, if you want to know what England is like, you have to leave it.