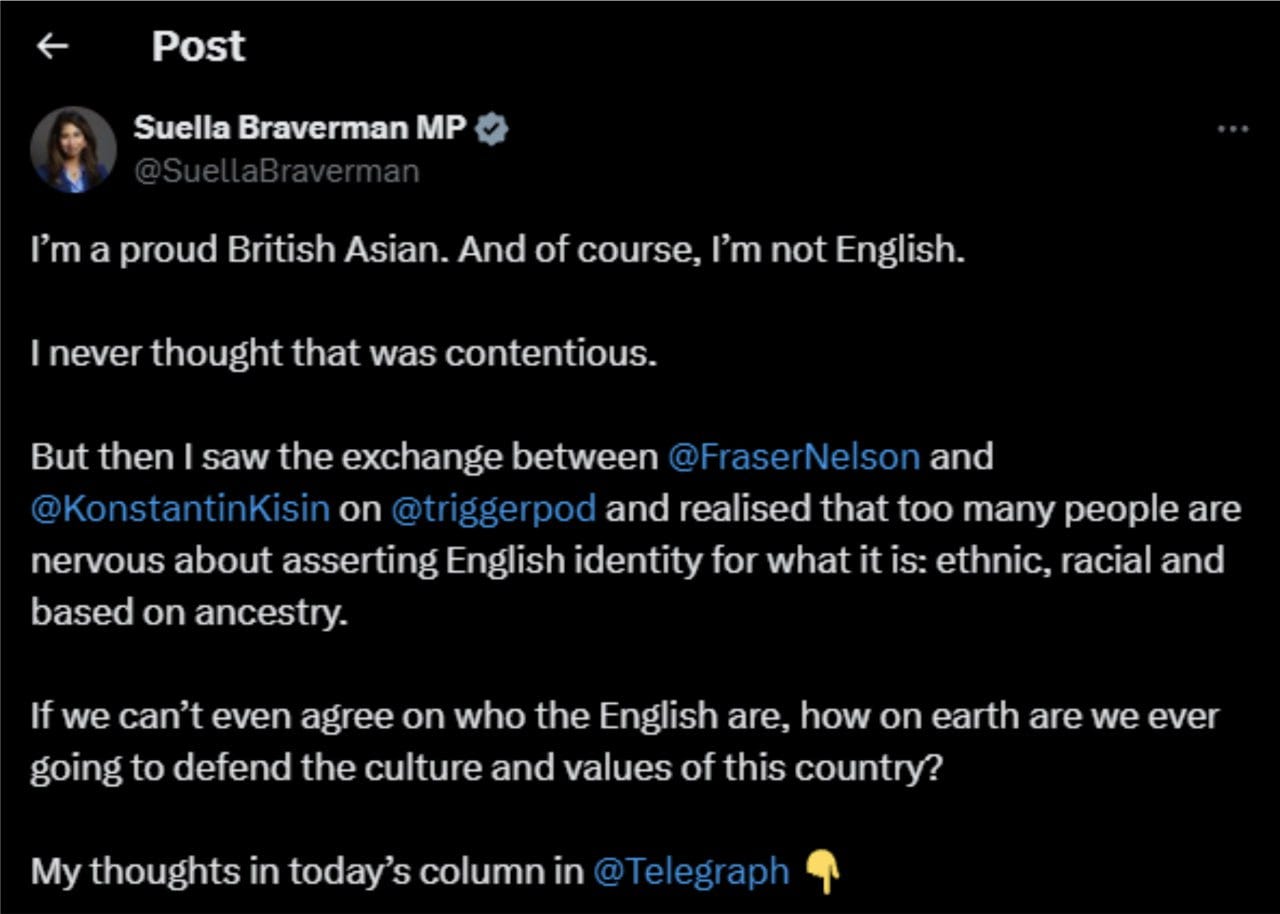

In a welcome development, Suella Braverman MP acknowledged the English as an ethnic group. In her Telegraph article titled: I will never be truly English: here is why, she states: ‘For Englishness to mean anything substantial, it must be rooted in ancestry, heritage, and, yes, ethnicity- not just residence or fluency.’

Braverman's comments come in response to a recent debate between commentator Konstantin Kisin and the former editor of The Spectator Fraser Nelson. Kisin said he is not English because English is an ethnic identity, and his parents are not English. Incredibly, Nelson claimed that anyone born in England is English.

Nelson betrayed a shocking lack of understanding of ethnicity and nationality. Before delving into the Braverman piece, brief and correct explanations of ethnicity and nationality are relevant. Ethnicity and nation are not identical, but we can often use the terms interchangeably without creating much ambiguity. Oxford Languages defines ethnicity as: the quality or fact of belonging to a population group or subgroup made up of people who share a common cultural background or descent. English ethnogenesis began in the late fifth century. It came with the fusion of Celtic and Saxon peoples. Relatively small-scale influxes of people who came to the British Isles from that time up until World War II were absorbed into an extant collective. There was no replacement of the population descended from the early Britons and the northern European tribes. The eye-watering scale of demographic change in the modern era does not alter the fact that the English people of today are the product of this ancient heredity. DNA testing shows this. This is not to say the English or any other ethnic group are a pure kind of anything. Nonetheless, English ethnicity is as valid as any other.

How does nationality differ from ethnicity?Oxford Languages defines a nation as: a large body of people united by common descent, history, culture, or language, inhabiting a particular country or territory. Nationhood entails the ethnic dimension of common descent and cultural background. Nations are groups who have developed these features into something more complex. A distinctive collective memory and a culture composed of specific political systems, art, literature, habits and customs are some features of a nation. A common language speaks to this coherence. Nations often have a territory organised in a culturally discernible way. We can simplify the distinction between ethnicity and nationality by noting that an ethnicity reflects the reality of a people with a shared heredity, and the nation represents their collective expressions.

Braverman begins her piece by noting an identity crisis in Britain caused by mass immigration and cultural fragmentation. She says the question of ‘English identity remains profoundly unsettled’. She is wrong here. English identity is settled but constantly gainsaid and denigrated. Simultaneously, any act of English self-definition not inclusive to the point of nullity invites the charge of “racism” and attempts at suppression. Perversely, elites and various commentators often show enmity to the English while denying us the right to identify ourselves. This denial is maintained via the nation of immigrants canard and nonsense spoken by people like Fraser Nelson. In his case, I suspect his stance can be attributed to liberal views and a lack of understanding rather than malice.

Braverman continues: ‘Englishness has never been static or simple. From the arrival of the Romans to the waves of Saxons, Vikings, and Normans, English culture has always absorbed and adapted.’ The first sentence from the excerpt is fair enough. The English, like other groups, have not always existed in a silo completely separated from other peoples. Then comes a clanger. The Romans came to Britain before the Saxons and withdrew in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. Braverman makes a glaring historical error and assumes the existence of an English culture before the arrival of the Saxons. The Saxon presence is intrinsic to the emergence of the English. Fortunately, her article gets better.

Braverman observes that English identity is ‘strangely muted’ and points to the institutions of empire as defining features exported so successfully that they no longer feel distinctly English. This point is not lost on people who find that the imperial project downgraded English identity in some ways.

She believes a failure to define Englishness is at the heart of a crisis and cites the usual fears of political leaders hesitant to appear nationalistic or xenophobic. Braverman argues this timidity has diluted English identity with the result that anything qualifies. ‘In Fraser’s world, all it takes to join the tribe is a plane ticket and a birth certificate.’ Braverman argues that this liberal tendency ‘explains why there are neighbourhoods in England where English is irregularly spoken, Western dress is abandoned, women and girls are subjugated and loyalty to Britain is not just absent but often opposed.’ The refusal of our leaders to recognise English identity does not alone explain distinctly foreign ways persisting in England, but Braverman gets at something. If the state under which the English live refuses to acknowledge English ethnicity in a positive sense, then it is unsurprising that recent arrivals meet the English and their ways with indifference and contempt.

Even if we had a pro-English government, Balkanisation would not end with the reassertion of English cultural identity. If the British state were to honestly restore the primacy of English culture and its writ in England, the differences between the English and other groups would be further magnified. An easy solution does not exist. However, an approach of the kind favoured by Braverman would encourage acculturation and the relegation of foreign ways within England. The English would generally feel more comfortable if this came to pass.

Braverman writes about her own cultural and racial identity and makes the obvious point that it is not English. ‘I cannot claim to be English, nor should I. This is not exclusionary- it is honest. And it’s what living in a multi-ethnic society entails'. This makes sense. If other groups are allowed to self-define along ethnic lines, then it is only fair for the English to do the same. The problem is that decades of brainwashing have led many English people to believe that they have no identity or that if it exists, then it is uniquely bad. With the change in tack advocated by Braverman, the situation could change more quickly than many people realise.

The former Home Secretary discerns the conflation of nationality and citizenship. It manifests with talk of someone ‘‘becoming British’’ after completing a citizenship test. Citizenship is a bureaucratic device. Nationality is something more fundamental and cannot be conferred. The MP understands this. ‘We have allowed what once made England distinctive to be diluted, denigrated, and demonised. Now, more than ever, we must define what it is we are fighting for – before it slips away entirely.’ Braverman’s article binds the rightful identity of England to the English people; this is its best service. If her words make it harder for the usual suspects to belittle and condemn the English for expressing themselves in a self-referential way, this will be very welcome.

All subscriptions, likes and shares are very much appreciated.

References

Suella Braverman, I will never be truly English: here is why, The Telegraph, 26/2/25, accessed: 28/2/25, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2025/02/26/i-will-never-be-truly-english-here-is-why-suella-braverman/

Triggernometry, Can Immigrants Become English? Konstantin Kisin vs Fraser Nelson, 18/2/225, YouTube, accessed: 1/3/25

Oxford Languages can be found here: https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/

Migration Watch, A summary history of immigration to Britain, updated 12/3/24, accessed: 1/3/25, https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/48

Legally, British Nationality rests on the principle of Ius Sanguini, the right of blood, so your nationality is determined by that of your parents, not where you were born, which is Ius Soli. This fact is completely missing from the debate, yet defines the British in law. It is why it was lawful to strip Shamima Begum of her British citizenship, despite her not holding a Bangladeshi citizenship: because her parents are Bangladeshi and in the eyes of the law, so is she. This applies to everyone in Britain with foreign parents, now. It is a matter of political choice that, for example, second generation Pakistani child rapists are not stripped of British citizenship. I surmise that the reason the Ius Sangini is omertà, is due to the inconvenient implications for our elite and post-WWII immigration.

I'm glad that Englishness has yet to be fuĺy bureaucratised.