The Alfredian Consolation

Alfred the Great was the ruler of Wessex from 878-99. He is most famous for defending Wessex against the Vikings and promoting education and learning. Asser’s Life of King Alfred, the earliest known biography of an Anglo-Saxon king, is one of the key sources for Alfred’s reign and describes how Alfred translated works from Latin into English[1] The king’s involvement in a translation project has been fiercely debated.

Historians have grappled with the question of whether Alfred the Great translated the works that have been at one stage or another attributed to him. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge have noted that Alfred is himself believed to be primarily responsible for four translations and his law code, the Domboc, Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, copies of which Alfred had circulated to churches; many are preserved to this day; Boethius’s Consolation, St Augustine’s Soliloquies and the first 50 Psalms of the Psalter. Gregory’s Dialogues, Orosius’ Seven Books of History against the Pagans, and Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica are said to have been prepared by scholars during the time of Alfred.[2] Historians who have written on this subject tend to more or less agree with the assessment by Keynes and Lapidge. The Alfredian translation programme was undertaken between 892 and Alfred’s death in 899.[3] Asser’s Life, which is the earliest known biography of an Anglo-Saxon king, is one of the key sources of Alfred’s reign. It was written in 893.[4] The piece below looks at the translation of Boethius’s Consolation.

Consolation

Maybe the most compelling translation attributed to Alfred the Great is that of the Consolation by Manlius Severinus Boethius. Boethius was a distinguished Roman and the father of two sons who had risen to the position of Consul. Boethius fell from grace reputedly due to pleading the case of Albinus, who was accused of treason against Theodric the Ostogroth king, who had become the sole master of Italy. It was whilst in prison that Boethius wrote the Consolation before he was executed[4]

The Consolation contains an omnipresent dialogue between Boethius and an entity called Philosophy. Boethius laments his forlorn situation when Philosophy comes to him; his property had been taken and he had been condemned to death without hearing. Philosophy asks Boethius if he thinks this world is governed by chance. He responds that God governs the world and says that he doesn’t believe things things happen like that[5] This statement sets the tone for a deeply philosophical work in which Philosophy advocates the pursuit of virtue and wisdom over concerns with more worldly desires such as fame and material wealth. The Consolation is not explicitly Christian in that it does not provide clear instruction in faith and belief, nor does it point to Christian saints or figures. However, Alfred’s adaption of Boethius shapes it in a Christian context, as we shall see.

Boethius admits to feelings of dissatisfaction even when he was in the possession of riches.[6] The work offers a critique of placing a high value on material assets.[4] The Consolation strives to demonstrate to the reader that, amid severe adversity, solace and true meaning can be found. This can be understood in the context of Philosophy criticising the high estimation placed on the worldly things once possessed by Boethius, such as high office, over that which lies within him as a person.[7]

Boethius bemoans that the virtuous are supplanted and set upon by the wicked. How can God allow these things, Boethius asks? Philosophy assures him that God sees to it that justice is done, the good has a reward, and the bad are punished and corrected. Good men seek the highest good through virtue, bad men by cupidity Philosophy says. The wicked are more to be pitied if they escape with unjust impunity. Philosophy tells Boethius it is down to him to choose how he shapes his fortune and therefore, even in the most challenging circumstances, the condemned Boethius is portrayed as possessing some agency over his spiritual wellbeing.[8]

The essence of Boethius’ work is preserved in the Old English translation, but a fair degree of deviation and freedom from the original text is in evidence. Instead of the dialogue being between Boethius and Philosophy, it is recast between ‘Mod’ or Mind and Wisdom.[9] This substitution of Wisdom for Philosophy is in keeping with the approach one would expect Alfred and his collaborators to adopt, given that the works of the translation project are replete with references to improving knowledge and becoming wise.

If it was indeed Alfred that selected Boethius to be translated, he chose a work that was widely esteemed and known during his time. The Consolation’s critique of material possession and fame is commensurate with the pursuit of wisdom that Alfred desired his subjects to undertake, as is the elevation of true virtue over cupidity. The substance of the discussion of kingship in the Consolation has led Malcolm Godden to suggest that Boethius’ critique of kingly authority is a factor positioned against Alfred’s authorship.[10] This interpretation may be a bit rash, however. The discussion of kingship and its inclusion in the English translation is one among other examples in the Consolation where the attainment of something deemed desirous is shown to produce problems. Looking at the work from this angle, the focus on kingship fits into a more general dichotomy in the work involving the attraction of worldly allures as set against more spiritual and truer virtues.[11] It is also worth considering that the context in which the Consolation was written is different from the Alfredian one in which it was translated. Alfred’s translation project began during a time of respite from the incessant Viking raids which had affected his reign. The people of Wessex had fallen behind him in battle and coalesced around him as a leader. He was in a position of strength. Furthermore, the divine right of kings is not questioned in the Consolation, so the discourse on kingship does not undermine the legitimacy of royal authority.

The Old English version of Boethius’ work contains many interpolations. In chapter 17, Mind tells Wisdom that covetousness and earthly power have never well pleased him. This is yet another example in the Alfredian corpus where the temptations of the world are warned against or counter-signalled. Mind then speaks of being ‘‘desirous for materials for the work I was commanded to perform’’. [12] The necessity of praying-men, soldiers, and workmen is then noted before necessary materials for the provision of the three classes are listed among those things that a king needs. These are land for habitation, gifts, weapons, clothes, meat, and ale.[13] The requirements detailed for the exercise of kingship in dialogue seem to be a way in which Alfred himself is positioned in the narrative by way of allusion. The translation is situated within the social structure of English society when the three classes are mentioned.

Boethius’s work contains passages that critique the value seen in the attainment of fame and warn of its impermanence.[14] Interestingly in this chapter of the translation, in contrast to the warnings in Boethius’ work relating to fame, Mind says, ‘‘Therefore I was desireth of materials wherewith to exercise the power, that my talents and fame should not be forgotten, and concealed’’. ‘‘This is now especially to be said; that I wished to live honourably whilst I lived, and after my life to leave to the men who were after me, my memory in good works.’’[15] Here Mind clearly expresses a desire to achieve a legacy and be remembered in the future. The reader of the translation can get the sense, given what appears an earlier allusion to Alfred in the chapter, that Alfred’s ambition, perhaps best epitomised by the translation programme itself, is being voiced here through Mind. The quote above is an affirmation of the pursuit of renown and likely an insight into Alfred’s preoccupations at the time the Consolation was translated.

Unlike the original which ends in a staid manner, the Alfredian Consolation ends with a prayer to the Christian God with pointed references to the sign of the holy cross and saints. Mind pleads to God to be strengthened against the ‘‘temptations of the devil,’’ which include ‘‘impure lust and all unrighteousness’’. Mind is also made to ask God for protection against both visible and invisible enemies.[15] As in the interpolation in this translation recollected above, it is not hard to envisage the person of Alfred in the guise of the literary adaption of Mind. The direct appeal to God and saints further underlines the Christian character of Alfred’s rendering and serves to affirm the focus on faith that suffuses the translation programme. The appeal to God for protection against sexual temptation and the perils therein is a common refrain of the Alfredian corpus and reveals to us an initiative to uphold standards of morality among the churchmen and nobility to whom the translations were directed. This common appeal to the divine to ward off temptations of the flesh may very well have been an appeal made by Alfred himself, asking for assistance amid the challenges of worldly office. The appeal for protection against enemies is congruent in a time of Viking incursion and the threat this represented.

The Consolation, like the Alfredian Soliloquies, can be interpreted as very personal and introspective. The choice of the Consolation for translation also reflected a selection of a well-recognised work. Its discussions of the vicissitudes of life may very likely have struck a chord with Alfred amid victories and defeats in battle. And as discussed above, an interpolation in the translation of the Consolation has Alfred express an open desire for his ‘‘talents and fame,’’ not to be forgotten. This alteration is at odds with the overarching message of the original text and can be read as an example of Alfred commandeering Boethius’s work in a way conducive to the designs of his kingship.[17]

Hello all, owing to some technical issues with my laptop I have had problems completing my piece on St George and his relation to the English in time for today. I do expect to be able to publish it soon enough, definitely before the 23rd of April. I hoped you enjoyed the piece above. It was first published on a different platform. I originally intended to publish it at The Heritage Site sometime in the future but reasoned given my technical travails that it would be apt to share it today.

Share your thoughts with me at adammcdermont89@gmail.com

References

[1] Simon Keynes & Michael Lapidge, Alfred the Great, Asser’s Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources, Harmondsworth, 1983, 99, 53 [2] Ibid 29-30, 162 [3] Frank Stenton, Anglo Saxon England, Oxford, 2001, 272 [4] K&L 48, 41 [5] Samuel Fox, King Alfred’s Anglo-Saxon Version of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, Cambridge-Ontario, 1864, 2 [6] L.V Cooper, Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, London, 2009, 15 [7] Ibid 31 [8] Ibid 22-24 [9] Ibid 23, 25 [10] Ibid 46-52 [11] Fox 3 [12] Godden 13 [13] Cooper 5-72 [14] Fox 36 [15] Ibid 36 [16] Cooper 25-26 [17] Fox 36 [18] Ibid, 122 [19] Ibid 36

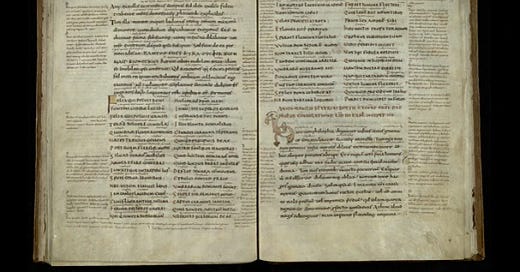

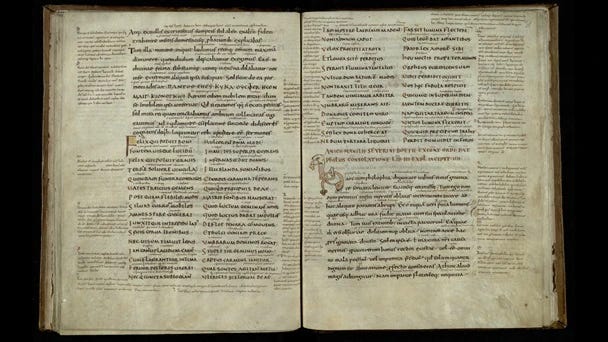

For information on the manuscript of the Alfredian Consolation visit: Boethius in Old English - The British Library (bl.uk)