National celebration ensued when Chloe Kelly’s late goal against Germany secured the first ever European Championship for English football on July 31st, 2022. This was a monumental moment. Unfortunately, not everybody tasked with reporting on the tournament greeted the success with unreserved enthusiasm. The sanctimonious apostles of the far-left and the globalists could not contain their dissatisfaction with the racial composition of the triumphant team. The deeds of specific actors, and those who give them voice, reveal untoward intentions, worthy of our notice.

Speaking after England’s 8-0 triumph over Norway in the group stages of the championship, BBC presenter Eilidh Barbour wailed, ‘‘‘All starting 11 players and five substitutes who came onto the pitch were white, and that does point towards a lack of diversity in the women’s game in England.”’

Any unalloyed joy following the win had to be stifled and the white character of the team pointed out. This ‘‘whiteness’’ was designated as a deficiency tarnishing English football. It did not matter to Barbour that non-whites were not eschewed on colour grounds. The team’s white predominance was heresy. We need not be detained by matters of sporting merit.

The side that featured against Norway was all white but this fact does not support a claim of ‘‘a lack of diversity in the women’s game in England’’. A mainly white national squad cannot be a barometer for the representation of non-whites in the women’s game given current demographic realities. According to the 2011 Census, the white-British population of the UK amounted to just over eighty per cent of the total. Whites as a whole comprised eighty-six per cent of people in the country. If for the sake of argument, the white-British population of the UK was just seventy-five per cent, a largely or entirely white England line-up would still not be very unlikely.

In June 2020, Fadumo Olow reported in The Telegraph that ‘Only 10 to 15 per cent of players' in the Women's Super League’, (WSL) the English top flight of women’s football, ‘are black’. The use of the word ‘only’ was disingenuous. The 2011 Census recorded the black population of the UK to be three per cent of the total. The WSL over-represented black footballers by three to five times in 2020, according to The Telegraph piece. The black demographic is unlikely to have increased from three per cent of the whole in 2011 to ten to fifteen per cent today.

It would be reasonable to think that those at the helm of women’s football in England have done enough over the years to warrant a favourable credit rating at the social bank of diversity. But this is not the case. Interest must be hiked.

In July 2022, a piece in The Athletic by Charlotte Harpur stated less than ten per cent of WSL players are ‘black, Asian or mixed heritage players.’ It may be the case that there has been a slight drop in the number of non-white players over the last couple of years. However, this is hardly a justification for an interrogation of the footballing authorities, especially given their track record of providing a platform for talented black players at the highest level. A graph in Harpur’s article demonstrates this (see below). In England women’s squads between 2005-2013, non-white players were selected above the proportion of the UK population which is non-white. The starkest example of this came in 2007 when non-white players comprised over twenty-eight per cent of the total. In 2015, 2017, and 2022, non-whites featured in proportion to the UK population that is non-white. In 2019, the percentage of non-white players was a bit lower than we might expect given the number of non-whites domiciled in the UK. Black players have been picked for England at a rate far higher than the size of the black UK population would seem to invite. It would be reasonable to think those at the helm of women’s football in England have done enough over the years to warrant a favourable credit rating at the social bank of diversity. But this is not the case. Interest must be hiked. Complaints were not put on hold for the sake of supporting the England team at the summer competition.

Three players who appeared to be of black heritage were selected in the twenty-three-player England squad for this year’s tournament, representing thirteen per cent of the total. Data from the 2011 Census indicates that non-whites were chosen in rough proportion to the percentage of non-whites living in the UK. This is not indicative of a “lack of diversity” as Barbour, Olow, and Harpur would have you believe.

Unwittingly, The Athletic chart above reveals an ethnic issue the publication is unlikely to address. An effect of England squads featuring non-whites above their share of the UK population was a paucity of white players, as whites were under reflected as per the proportion of whites in the UK. Did anyone consider white players who would have played for their country were it not for the over-representation of non-whites?

With obliviousness to how her words may be perceived, or with pride for an overtly pro-non-white attitude, Harpur wrote the following: ‘Stokes and Parris are the longest-serving non-white players who have featured for England in the last three major tournaments. It is a stark contrast to the men’s team, who last year, for the third consecutive competition, had a squad that was more than 40 per cent non-white.’ The forty per cent figure is presented only as a moral good. Why should such over-representation of non-white players in the England men’s team not raise questions about a lack of white-British competitors due to their under-representation in this example? Outlets like The Athletic will never bring themselves to view issues of race and ethnicity in such a way. As Harpur detected, the England men's squad has featured non-white players at a rate of over forty per cent, and the last Census recorded the non-white population of the UK as numbering nowhere near such a percentage. When this is understood, the possibility of an all-white England team is strong considering whites comprise eighty-six percent of UK residents according to the 2011 Census. The evidence Harpur uses to support her argument rebounds on her and supports the potential for white England line-ups.

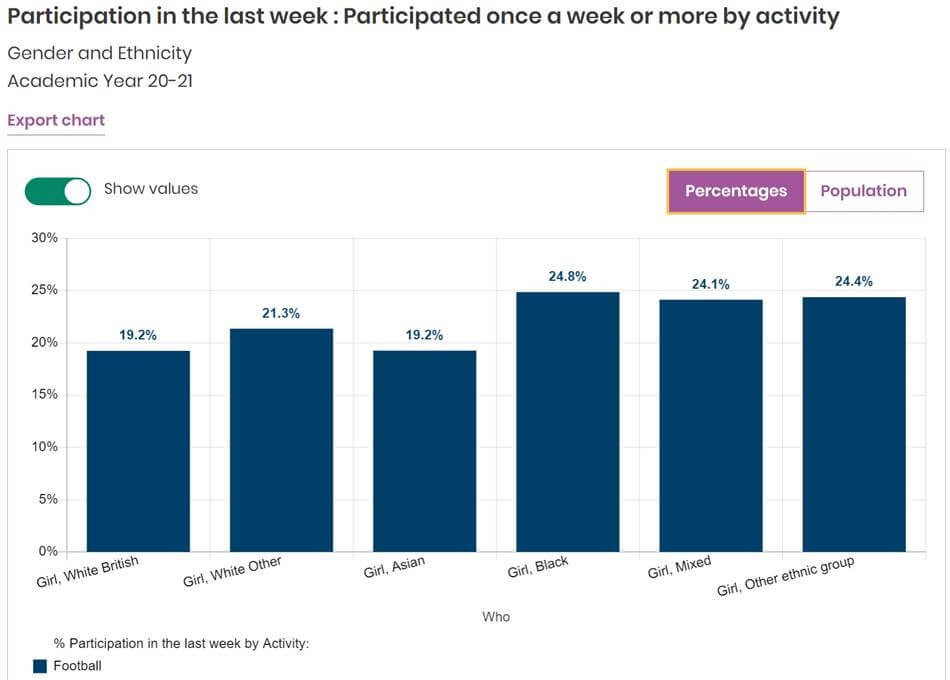

Another example of Harpur’s anti-white bias came when she reflected on grass routes participation in the UK women’s game. A graph reveals findings not supportive of the didactic purpose of her piece (see below).

‘According to the latest Active Lives Children and Young People survey (data taken from the academic year 2020-21), 707,200 girls were playing football from years one to 11. Twenty-four per cent of those were from Black, Asian or mixed heritage backgrounds.

‘What is interesting is that among their ethnicity group, there is a higher percentage of girls from mixed, Black or other ethnic groups playing football when compared to 19.2 per cent of White British children, equal to those with Asian heritage.’

These findings are ‘interesting’ but many of us will not see them as a development warranting acclaim. Harpur does not perceive any problem with white girls and their Asian counterparts being less likely to play football than other groups. Why should the research not lead to targeted initiatives encouraging white-British and Asian girls to play football? You will not be surprised that the next paragraph she writes after noting these statistics avoids this point. White ethnic interests do not feature in Harpur’s formulation.

The most galling aspect of the Harpur piece is strongly indicated by its title: ‘They don’t look like me. It’s off-putting’ – England women and a lack of non-white role models. She quotes Hannah Baptiste who works for the charity Football Beyond Borders. Baptiste played for England’s Under-16s and now features for Guyana’s senior team following a discomfiting experience in the UK. She said: ‘‘The French team; I love it, it’s beautiful. That’s what football should look like. Why are France able to get it right but we’re struggling when we’re such a diverse country?’’ The squad that figured for France at the Women’s European Championship contained fifteen non-white players out of the twenty-three-player total. Like the rest of Western Europe, France has experienced mass immigration in its recent history. Despite this fact, most people living in France are ethnically French. Baptise referred to the over-representation of non-whites in the France team and the concomitant under-representation of whites as ‘‘beautiful’’. As with the earlier examples, an empowered desire to see minorities over-reflected is evident, and so is a disregard for the ethnic interests of whites. She espoused a racial takeover. What do whites have to gain by conciliating such an interest aside from disinheritance?

Baptiste goes further, on playing for Guyana she said: ‘“I feel most at home when I’m playing football with them because the girls and coaching staff look like me”. Judging by these comments, being a minority in a majority white society is just too much for Baptiste. Her words appear to assign blame to whites for possessing white majority states. It seems only a complete erosion of white ethnic homogeneity could pacify this individual. Baptiste’s honesty is quite refreshing in a way. She has proclaimed a preference to associate with her racial and ethnic group. This is not a bad thing. It stands to reason in a fair society, white people can express similar views. This is significant, we will return to the point later on.

Like a devastating two-footed-lunge, racism scythed Nelson down, ending what would have been a remarkable career.

At halftime in the Finland v Denmark match on July 12, the BBC aired a programme on diversity in women's football. At the start of the show, Alex Scott identified a major transgression. Some England matches have not featured a single non-white performer. Scott was adamant that this should not be allowed to continue.

Scott met charity worker Debra Nelson. Where do you think Nelson works? If you guessed Football Beyond Borders, where she can count Baptiste as a colleague, then you are right. The group’s name is telling of a particular worldview, and so is the fact that their Chair Matt Stevenson-Dodd has been published in The Guardian.

Before the interview, Scott informed us that Nelson was a promising player before “racism” dissuaded her from pursuing professional football. Like a devastating two-footed-lunge, racism scythed Nelson down, ending what would have been a remarkable career. The BBC offered no room for doubt, although no description of any racism is provided. Nelson is a victim. The suggestion that she was subjected to racism was made to confer on her an unquestioned moral superiority from the outset of the segment. It seems unlikely that racism curtailed her beckoning stardom. Racism did not stop the over-representation of black athletes in the WSL in 2020, as stated by the Telegraph, and a relatively recent over-representation of non-white women in England squads, noted by The Athletic.

Scott expressed her concern following a social media post. Nelson had declared her anguish at not being able to identify with the England team. She told of an aversion to a predominantly white squad. After the post, Scott rushed to check on Nelson's welfare. This was relayed in a matter of fact way. Scott and the BBC accepted the implication that the homogeneous make-up of the national team could cause mental harm to non-whites. Whites were portrayed as a health hazard.

Nelson told Scott ‘‘‘I feel like if someone doesn’t have the same lived experiences as you, isn’t of the same background of you, there are so many parts of people’s identity and if you can’t connect with at least one part of someone’s identity, how can they be your role model?’’’

Scott met Nelson at ground zero of this disaster. Nelson donned a hooded tracksuit, her choice of dreadful urbanite regalia. Inevitably, footage of graffiti laden street walls preceded the interview. The discussion was held in an undesirable locale, lest the BBC viewer understands anything but deprivation.

Nelson chose to publicise her angst at a majority white England squad. Her identity had to be salient. Sod sparing a thought for those who wanted to enjoy the performances of their compatriots. Nelson’s diversity concerns had to take precedence, even though there was no suggestion that talented black footballers were unduly omitted from the tournament squad.

Unsurprisingly, Nelson uttered today’s boutique platitude of ‘‘lived experience’’. A solid interviewer would have asked her, what experience is not lived? The piece passed without danger of Nelson being subject to critical enquiry. This is what your licence fee does for public discourse.

Nelson spoke of requiring a role model. Three players in the squad appeared to approximate her heritage. Her words regarding there being many parts to a person and the need to connect to the players’ identity are worth considering. Did she mean to say that she can only relate to a part of someone's identity if the person is of her race? She implied an answer in the affirmative. Perhaps something was lost in editing? Regardless, the BBC was happy to convey Nelson's view as highly predicated on race. This should cause those who obsequiously eulogise Britain's multicultural society to have a deep think. What could the consequences of Nelson's line of thought be for “integration’’, “celebrating our differences”, “tolerance”, “community cohesion”, and all the rest of it?

A more acceptable complaint than Nelson's could be made by whites throughout Europe. In some football line-ups, whites are not prominently reflected; the France women’s team has already been noted. The France men’s 2018 World Cup winning team was noticeable for its small minority of ethnically French players. The demography of the squad compelled Al Jazeera to ask the question, ‘Did France And Africa win the World Cup?’Many who remember that tournament will recall stands teeming with white French supporters cheering mainly non-white players. If the fans had any racial grievances, they seem to have put them to one side. Nelson did not choose such a course.

Do not expect the BBC to offer fawning interviews with disgruntled French whites who might speak about the ‘‘diversity’’ of the France side. Do not expect the BBC to garner the thoughts of white Brits on the composition of the England 4 x 100 relay team at this year’s Commonwealth Games. Do not expect them to ask American whites about the fabric of the NFL and the NBA.

To be continued in part two…..

Subscribe to The Heritage Site for free to receive new posts and to support my work.

HISTORY, HERITAGE, CULTURE

References

BBC presenter Eilidh Barbour: England soccer team 'too white' (nypost.com)

Only 10 to 15 per cent of players in the Women's Super League are black — what is life like for the minority? (telegraph.co.uk)

2011 Census analysis: Ethnicity and religion of the non-UK born population in England and Wales - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

‘They don’t look like me. It’s off-putting’ – England women and a lack of non-white role models - The Athletic

BBC defends Alex Scott's report into lack of diversity in women's football | Metro News

BBC iPlayer - Alex Scott: The Future of Women’s Football

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/nov/06/sports-charity-better-open-failure

Did France AND Africa win the World Cup? | The Stream - YouTube

England defend men's 4x100m title (birmingham2022.com)

https://register-of-charities.charitycommission.gov.uk/charity-search/-/charity-details/5043801/trustees